By Zina Hemady

The first US overt military intervention in the Middle East took place 60 years ago, when the Marines landed on a beach just south of Beirut on a sizzling summer day. While Washington was responding to a plea by Lebanon’s beleaguered Maronite Christian president Camille Chamoun, whose government was facing a rebellion by a coalition of mainly-Moslem political opponents, the real motive for the muscle flexing was the overthrow of Iraq’s pro-Western regime while the popularity of Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, a Soviet ally, swept the region at the height to of the Cold War. This invasion, now tucked away in the folds of history, stands out as a swift and nearly bloodless operation with tangible results as compared to the more recent US military fiascos in the region. Many credit this accomplishment to level-headed diplomacy and collaboration between US and Lebanese officials to avoid all-out war.

Lebanese soldiers (L) and pro government Druze fighters (R) exchange gunfire with anti-government rebels in the Chouf Mountains southeast of Beirut. Norbert Schiller Collection. Phot. AP Wire Photo

The intervention, code named Operation Blue Bat, had no clear military objectives besides making the beach landing, seizing the airport, and moving into the city. Moreover, the plans originally made jointly with the British military kept shifting until the last minute when President Dwight Eisenhower decided that his troops, a combined Marine and army force of 14,000, would take on this mission single-handedly and with half the 24 hour warning time that he had promised the commanding officers.

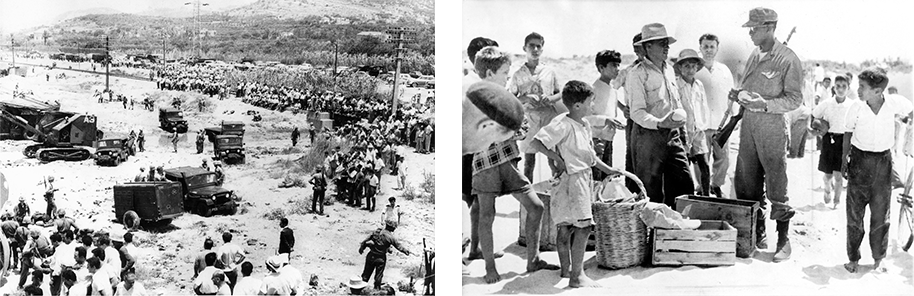

After landing on Khaldeh beach the Marines secured the airport so that transport and other military planes could land there. Phot.(L) Chuck Smilie, (R) Norbert Schiller Collection, AP Wire Photo

1st Lt. Chuck Smilie on the ground in Lebanon. Phot. Chuck Smilie

Retired Marine Colonel, Charles Smilie, who goes by Chuck, was a First Lieutenant with the third of the three battalions of the Sixth Fleet which participated in the initial beach landing. The 26-year-old Marine and his mates were heading to Athens for a few days’ leave when “all of a sudden we thought the boat was going to capsize when it made a sharp turn and started heading south to go to Lebanon.” They had never heard of the country nor did they know what to expect. “We were told that we were there to maintain order, maintain peace, but it’s not like we were given a whole lot of intelligence.”

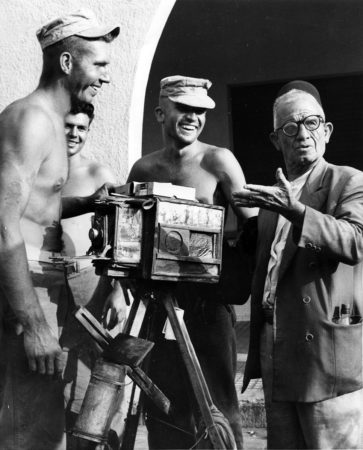

Despite the ambiguity and logistical challenges, the first contingent of the 6,000-strong Marine force to participate in this operation successfully landed on July 15 at Red Beach, just north of the town of Khaldeh and half a kilometer from Beirut International Airport. The scene that the “leathernecks” encountered was far from the hostile scenarios that some had been apprehending. Ironically, it was the Marines who startled the locals made up of villagers carrying out their daily chores, construction workers, and bathers taking a break from the capital’s stifling summer heat. Curiosity drove these onlookers to converge onto the landing site where young boys even helped the Marines unload some of their heavy equipment as their wheeled vehicles got bogged down in the soft sand of the Lebanese coast. Street vendors popped up at the beach offering to sell their wares to the Americans.

A carnival-like atmosphere followed the Marines landing at Khaldeh Beach south of Beirut. Street venders set up shop selling the Marines everything from Coca Cola to carpets. Norbert Schiller Collection, Pho. (L) AP Wire Photo (R) UPI

Armed Rebels, one of them a woman, crouch behind a barricade in the rebel stronghold of Tripoli. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. UPI

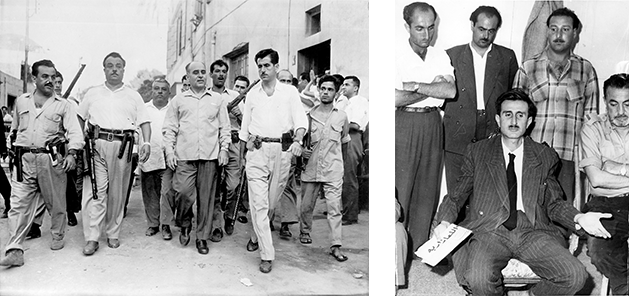

These displays of normal life in times of turmoil, which would characterize Lebanon even during the bleakest days of the civil war that erupted nearly two decades later, did not downplay the seriousness of the crisis. The conflict was complex, with local, regional, and international implications, which seems to forever be Lebanon’s predicament. Internally, President Chamoun, who was nearing the end of his non renewable six-year term, had come under fire by his opponents for having allegedly manipulated the parliamentary elections of June 1957 to guarantee a legislative body that would amend the constitution to allow his reelection. The poll results, which heavily favored Chamoun, sparked riots and solidified the standoff between the president’s supporters and opponents. Although the two camps included leaders of different religious affiliations, many Christians stood by the president while most Moslems wanted him to step down. The most vocal opposition heads who would later emerge as the rebellion leaders were Saeb Salam, a Beirut Sunni, Kamal Jumblat, a Druze from the Chouf Mountains, and Rashid Karami, a Sunni from Tripoli. The regional and international contexts to this situation were the rivalry between the pro-Western Baghdad Pact and the pan-Arab movement led by Egypt and backed by the Soviet Union. Chamoun had refused to break relations with Britain and France after the 1956 Suez War when the two former colonial powers sided with Israel against Egypt. Subsequently, he supported the Baghdad Pact feeling the pressure from Egypt’s union with Syria in what became known as the United Arab Republic. Both these moves angered his opponents who saw them as a stab to Lebanon’s Arab identity.

Gun-toting rebels accompany their leader Saeb Salam to a meeting with US envoy Robert Murphy (L). Druze leader Kamal Joumblatt, who was heading the rebellion against the government in the Chouf Mountains speaks to the press from his hideout. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. (L) AP Wire Photo, (R) Keystone Press

Although the United States was keeping a close eye on developments in Lebanon, the real catalyst for the military intervention was the Iraqi Revolution of July 14, 1958. Army officer Abdel Kareem Kassem led the coup d’état which overthrew young King Faisal killing him and Prime Minister Nouri es Said. The violent events in Baghdad, the only Arab member of the pro-Western regional alliance, sent shock waves to Washington and Beirut. As the US leadership was considering the options to protect its strategic interests in the region, not least of all were Iraq’s oilfields, Chamoun invoked the Eisenhower Doctrine under which the United States would send military and economic aid to any Middle Eastern country threatened by communist aggression.

An elderly street photographer jokes with marines in Beirut about having their picture taken. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. UPI

When the Marines made their landing at Khaldeh, their leadership was aware of the risks involved. The rebels, a lightly armed 10,000-strong force split into different factions, posed a benign threat, while the more significant danger came from the Syrian First Army which consisted of 40,000 troops equipped with Soviet tanks. However, as it turned out, the Syrians stayed out of the conflict except for facilitating weapon transfers to the rebels, and it was the Lebanese army which constituted the greatest diplomatic challenge to the Americans. From the beginning of the crisis, Army Chief General Fouad Chehab’s greatest concern was that the army would break up along religious lines, which is what happened during the 1975 Civil War and led to the country’s disintegration. Chehab had so far contained the situation by allowing the insurgents to protest, while at the same time keeping them in check. With US boots on the ground, the general was now worried that the United States would be perceived as an occupying force.

Using his good standing with Washington and Cairo, Chehab played a key role in maintaining stability and he did so in close coordination with US officials. When he heard of the landing, the army chief appealed to US ambassador Robert McClintock to send word to the Marines to reboard their ships. However, the request was turned down by one of the battalion leaders and the landing force proceeded with the plan to capture the airport and move into the capital. Confirming Chehab’s fears, a Marine column headed north from the airport to Beirut was stopped at a Lebanese army roadblock where soldiers aboard tanks stood ready to fire at the Americans. The situation was defused at the last minute when Chehab, McClintok and Admiral James Holloway who commanded the entire operation appeared at the scene. They immediately went into intense negotiations at a nearby school where they hammered out the agreement that would define the relationship between US forces and the Lebanese army and clarify the US’s military role in this intervention.

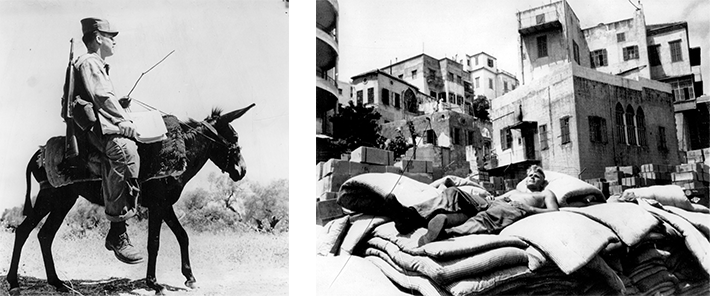

A soldier makes his rounds on a locally-purchased donkey delivering the Stars and Stripes newspapers to his fellow combatants. A Marines takes a nap on top of supplies at a depot in the center of Beirut. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. (L) AP Wire Photo (R) Bill Sauro, UPI

It took about a week for the two sides to finalize their agreement, and in the meantime the situation on the ground was still precarious as all sides continued their political maneuvering. In addition to the airfield, the Marines took control of Beirut’s dock area and some strategic bridges leading to the city. However, their most vulnerable position was the airport, where traffic had intensified with the landing and take off of military planes airlifting Marines and army troops. Rebels positioned in nearby hills fired towards the airstrip, but their pot shots proved largely harmless. In the city itself, two Marines on patrol lost their way and strayed into the rebel stronghold of Basta where they were kidnapped and released a few hours later. On the political front, Chamoun continued to press the Americans to interfere more aggressively to quell the rebellion and eliminate any regional threat to his regime.

US Deputy Undersecretary of State, Robert Murphy (L) and US Ambassador to Lebanon Robert McClintock (R) meeting with Lebanese President Cammille Chamoun. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. AP Wire Photo

Amid this state of uncertainty, Eisenhower sent Deputy Undersecretary of State Robert Murphy to Beirut. While his initial mission was to address the tensions between the military and the US Embassy officials, which turned out to have been defused, Murphy quickly turned his attention to the Lebanese situation. After shuttling back and forth between the different parties, the emissary determined that the country’s internal strife was a local issue which should be handled as such. He gave the rebel leaders assurances that the US military’s presence was not intended to keep Chamoun in power which promptly defused the situation and reduced attacks against the Americans. Moreover, Murphy openly declared his support for immediate presidential elections, a call which was surprisingly heeded by Chamoun without resistance. While the US envoy addressed the political crisis, Chehab and the US command reached an agreement stipulating that the Marines would be positioned north of the capital and the US army to the south,while Lebanese soldiers created a neutral zone between the US troops and the rebels in Basta.

As the country prepared for the July 31 presidential vote, the Marines settled into a routine which would characterize the remainder of their brief venture into Lebanon. Smilie, the Marine pilot who landed on the second day of the invasion, said that after a week at the airport, where he coordinated air traffic with Lebanese tower control officials, he was transferred to a camp in a pine forest near the hillside town of Beit Meri north of Beirut. “This wasn’t war. We spent a lot of time sitting on our duffs doing nothing trying to spur out some fun,” he recalled. To pass the time, Smilie and his buddies would venture to the local restaurant in Beit Meri or barrel down the hill to Beirut where they hung out at the pool of the Commodore Hotel, the beach of the Bain Militaire, and off course the iconic bar of the Saint George Hotel. To keep up with their training, and maintain their sanity, they flew sorties over Lebanon for about four hours a month.

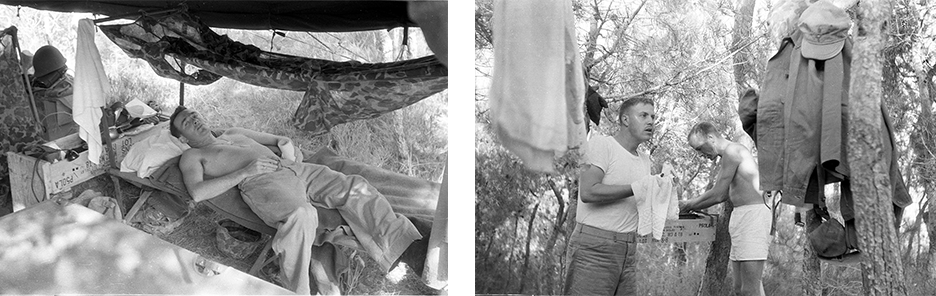

First Lt. Chuck Smilie, suffering from Dysentery, lies on his cot holding a roll of toilet paper near the village of Beit Meri in the foothills north of Beirut. Dysentery and boredom were the biggest threats that the US military faced in Lebanon. Fellow Marines 1st Lt. Jack Manroe (L) and 1st Lt. Bob Baughman wash up in their makeshift bathroom amid the pine trees. Phot. Chuck Smilie

By mid-August, the first troops began to pack up and board transport ships leaving Lebanon. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. UPI

Although the rank-and-file were largely oblivious of the political complexities of the crisis and its potential dangers, their predicament could have been bleaker had it not been for the open cooperation between the US command, American diplomats, and Lebanese officials namely Gen. Chehab. By the end of Operation Blue Bat in late October, one US soldier had been killed and one wounded by the rebels, while the two recorded Marine deaths were due to friendly fire. This was considered a glaring success compared to the next US deployment in Lebanon after Israel’s 1982 invasion when 220 Marines and a dozen service personnel were killed in an attack on a Marine compound near the airport. For Lebanon, the 1958 US intervention facilitated Gen. Chehab’s ascent to the presidency ushering in an era of nation building and prosperity which would become known as the Golden Age.

Nice article Zina!

One thing that was not brought to the fore was Abdel Nasser’s desire and drive, overt or subtle, to swallow Lebanon into the UAR. The Chamoun reelection claim, real or false, was a useful pretext.

….but you already knew I’d be saying this!!!

Wonderful and revealing article Zina thank you

Timur Tengah Bergolak, Amerika-Inggris Melakukan Intervensi dalam Krisis Di Lebanon dan Yordania Tahun 1958 - Sejarah Militer

[…] Operation Blue Bat: The 1958 U.S. Invasion of Lebanon […]

July 15, 1958, 3 AM the sirens went off and my unit (C Company, 1st Battle Group, 18th Infantyr Regiment, 1st Infantry Division) was put on alert as part of Operation Blue Bat. We were told to “stand down” at 5 AM because the Marines had landed. Thanks to all the Marines that served there in my units place.

CW3 Alfred F Tenuta, AUS Retired

I was there as supply Coordinator to insure the 3/6 had what the needed from amo to food, equipment and even Beer when they could have a break.

I was with 3/6 2d SvcBn how do I get a picture of that landing craft I landed off KA 107

I am not sure that was my landing craft that is why I would like a bigger picture so I could see better the Marines who were in it I landed off the USS VERMILION AKA 107 I would like to see a clearer picture I would glady tell of my experince of what I recall

URL

… [Trackback]

[…] Informations on that Topic: photorientalist.org/exhibitions/operation-blue-bat-the-1958-u-s-invasion-of-lebanon/article/ […]

I was 18 years old. Our group entered inside an amphibious tractor offloaded from an LST. We were carried directly to the airport and when the front ramp opened there seemed to be many planes in the area. We moved across the runways to a drainage ditch. While in the ditch planes began landing routinely. Later we began a slow movement into Beirut and for awhile it became a combination of standing guard with tanks on some bridges plus work details to unload our ships. C-rations were stored in a fenced in area near Muslim apartments. Today, August 19, 2021 I read an article about Afghanistan women tossing their babies over the fence at an airport to be rescued by American forces. This is what reminded me of our Beirut experience because the same thing happened in the compound where we were stacking our C-rations back in 1958.

I had a friend who was there, Ronald Russell USMC. Just wondering

I was there on July 15th, got extended because I was on a Med. Cruise and was scheduled to be discharged on July 10th, 1958.

Landed on the beach with 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, 2nd Marine Division. Since 20 of us were short timers, we flew home to Camp Lejuene, NC to be discharged by Aug. 8th, 1958….Most of us were from Phila., Pa…Long ago, Semper Fi.

Thank you for this article. I am the first grandson of Ambassador Robert McClintock. If anyone has a story he’d like to share with me about my late grandfather, he can find me on Facebook and inbox me directly. I live in Los Angeles, I’m a screenwriter, and I’m deaf. I’m currently working on a movie project.

I was in the 79th Engineering Battalion, Co. C in Pirmasens, Germany in 1958. We were given orders to prepare our equipment for seaboard transport to an unknown destination. As seems typical for military orders this was an on and off again effort apparently due to political considerations that a typical GI like I was had little understanding of at that time.

Ultimately our group loaded up and traveled by ship departing the port in Bremerhaven, Germany. We endured the long trip down the coast of Europe and through the length of the Mediterranean to Lebanon. Along the way a Russian submarine surfaced off the starboard side and gave us the jitters. We landed at the port in Beirut where it was obvious that this was not another D-Day. We were transferred to an olive grove by Lebanese buses that were painted and decorated better than any military vehicle could ever be. We set up in the olive grove, lived in tents and as would be expected by an engineering group found a way to make ourselves comfortable. Since we had equipment and many skilled hands, within a week or so we had hot showers, a first class mess area and before long we were hosting boxing matches at night between all of the different service organizations associated with the “invasion”.

It was not a war in any sense that we generally consider war. The only firing that I was aware of was on my way back from downtown Beirut when a sniper started shooting at men and tanks that were set up adjacent to the road. The sniper was silenced along with a few watermelons at an intersection known as “Watermelon Circle”. After things settled down and we were able to go to town, I remember an R&R in a downtown hotel where I got to drink an American beer and saw for the first and hopefully the last time a fat belly dancer. The wonderful people associated with the American University of Beirut had a meet and greet and cookie event for some of us lucky ones and gave us a real taste of home.

I was a “short timer” and was able to fly out of the Beirut Airport and return to my base in Germany. This was to prepare our home site for the general return of all of the group that were so lucky as to come back by ship…! From Germany I flew to the US at Fort Dix after a brief stop in Goose Bay Labrador. On to Ft. Chaffe and then to home in Houston, Texas.

Not much of a war story but it’s the best I can do now that I am almost 90 years old…!!

Proud to be this man’s daughter and a fellow Army engineer!

Did you know William Thomas Looper. They may have called him Tommy? That was my dad. He as at Camp Lejuene NC. He was over there in Lebanon the same time.

No I am sorry that I do not know him. We tended to stay with our own units and did not have much opportunity to get around. I am sure your Dad was a fine man and I am happy to have served with him in Lebanon.

My uncle, Navy, told me he was injured in an explosion at that time. He was hospitalized with burns to his legs.

However, I am unable to locate his medical records. Could he be eligible for service connected injury?

Any help would be appreciated.