by Zina Hemady

On this second segment of The Nativity Trail we entered the heart of the West Bank crossing plains rich in springs, agricultural lands, valleys and mountain passes travelled by biblical patriarchs as they headed to the ancient city of Shechem, known to many as Nablus. We heard stories about the historical and spiritual significance of these sites as well as present day political and social conditions which make this part of Palestine so volatile.

From Zababdeh the trail heads south through olive groves and forested hills into the bread basket of the West Bank which is dotted with fields and green houses. Some of the produce and herbs grown here are exported to the global market, despite Israeli restrictions that have crippled the Palestinian economy, particularly the agricultural sector. However, the greatest challenge by far faced by Palestinian farmers, and for that matter the entire Arab population of the West Bank, is access to water. With the exponential increase in Israeli settlements which are carving up the West Bank, water has become a rare commodity. It is pumped directly from the sources to the Jewish population centers leaving the Arab areas helplessly parched. Nonetheless, some farmers tenaciously refuse to give up a tradition that started with their forefathers and attempt the impossible by trucking in water or using techniques that rely on efficient irrigation.

A photo of the village of Zababdeh alongside a 1880s photo of a village in the northern West Bank. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

As we trekked through fields of alfalfa, potatoes, cucumbers, tomatoes, and garbanzo beans (hummus), a Palestinian staple, our guide Nedal Sawalmeh explained how the Oslo peace accords have affected the residents of the West Bank, which was divided into three administrative areas. Area A is allegedly fully controlled by the Palestinian Authority, area B is under PA civil rule while security is jointly controlled by the Palestinians and Israelis, and area C, 60 percent of the territory, is under full Israeli control. Palestinian indignation against Israeli presence is a given, but there is also resentment against at the PA which is widely considered self-serving and corrupt. Some Palestinians go even further accusing PA security of conveniently clearing out of area A zones to facilitate Israeli military incursions into these Palestinian population centers.

A photo of a Palestinian farmer heading towards his fields in a tractor alongside a nineteenth century colorized photochrome showing a rural scene from the northern West Bank. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

The conversation switches back to history as we get closer to Wadi al Fara’a, home to the ancient site of Tel el Fara’a and the Canaanite city of Tirzah. Across from the ruins, which lie on top of a mound, is the al Fara’a refugee camp, one of the West Bank’s 19 settlements established in 1948 to house the Palestinians who lost their homes after the creation of Israel. Nedal, a Bedouin whose family originally hails from the village of al Sawalmeh near Yafa (Jaffa), was born in the camp almost two decades after his parents were forced into exile. His eight children were also born in el Fara’a which has now become a small overcrowded town of about 7,000 residents. In spite of his own struggles, Nedal has made sure that his six girls and two boys receive the best education possible to prepare them for the limited job opportunities available to them, and give them some hope for the future. After spending the night at Nedal’s house and feasting on a traditional meal of coussa bil laban (stuffed zucchini cooked in yoghurt) we headed southwest towards Nablus. On our way out, we ran into Nedal’s uncle who owns a hall used for banquets and wedding receptions. As he proudly showed us around his establishment, I sensed a suppressed melancholy in his eyes and demeanor. Nedal later told us that his cousin was serving a 17 year jail sentence in Israel for killing a collaborator. Sadly, tragedies of this kind were the norm among the people that we encountered along this journey. Every family had been touched by either death, injury, or incarceration.

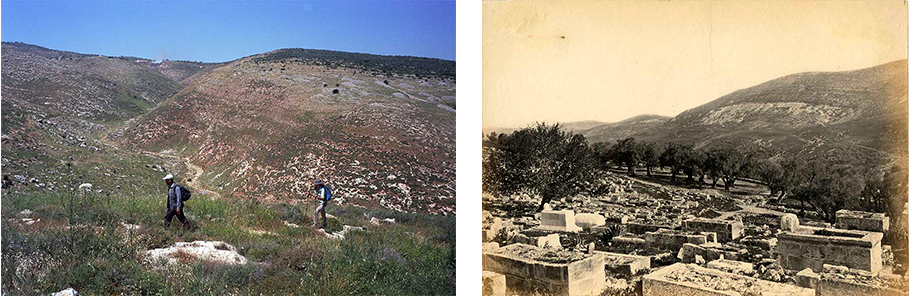

A photo of the foothills of Mount Gerizim beside a nineteenth century photo showing Mount Ebal. The city of Nablus is situated in a valley between the two mountains. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Frank Mason Good

This part of the trail is fraught with biblical sites culminating with Nablus both a major center of Palestinian activism and the first capital of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. To throw a spin to the historical claims to these lands, this area is also home to one of the largest remaining Samaritan communities who believe that Mount Gerizim (Jebel Jarzim), which towers over Nablus, is the place where Abraham went to sacrifice his son and the location chosen by God for the Temple. Because of the historical and political significance of this part of the West Bank, formerly known as Samaria, passions run high in these valleys and mountains which are home to some of the staunchest Jewish settlements on Palestinian territory. After Wadi el Fara’a we crossed Wadi Beidan, a valley that lies on the Way of the Patriarchs, an ancient route traveled by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the father of the twelve tribes of Israel. Walking up along a pass we were in full view of the settlement of Elon Moreh which has occupied a prize location at the top of Jebel Kabir since 1980. Its residents harass their Palestinian neighbors during the olive harvest, a common intimidation tactic practiced by settlers, or clash with them when they pass through their villages on their way to visit Joseph’s Tomb in Nablus. After we snapped a few pictures, Nedal warned us about the surveillance cameras and suggested that we don’t linger for too long. As we continued along the pass, he showed us where, during the Second Intifada, Israeli snipers shot at Palestinian workers and students as they headed to Nablus and al Najah University on these back ways after Israel had closed all roads leading to the city.

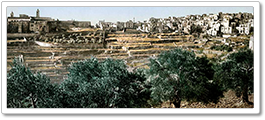

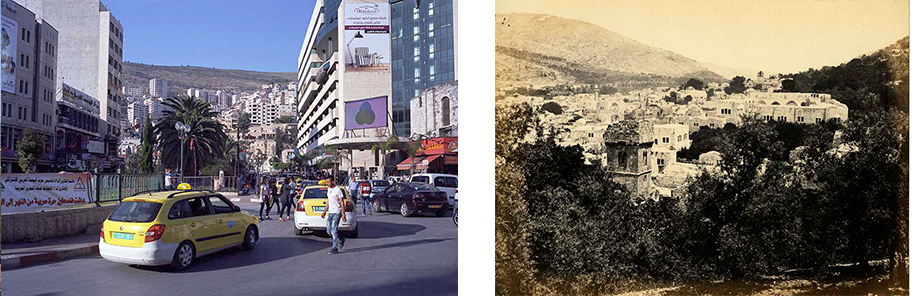

A photo of the central square in Nablus alongside a nineteenth century photo that shows Nablus between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Francis Frith

Across the valley we could now see Nablus nestled between Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal (Jebel Ibal). Although the city has spread considerably over the centuries, it is still distinctly recognizable as the one depicted in the photos of nineteenth and twentieth century travelers because of its location between these two mountains, known in biblical tradition as the mount of blessings and mount of curses. After the destruction of Shechem, the Romans rebuilt the city renaming it Flavia Neapolis, which then became Nablus. The Romans were succeeded by many other invaders including the Byzantines, the Crusaders, and the Moslems who have all left their mark. The city is also famous for being the center of the 5th and 6th century Samaritan revolts against the Byzantines after which the community was expelled from this area, returning several centuries later. The spirit of revolt is still very much alive in Nablus, also called Jebel en Nar (the Mountain of Fire) in recognition of its resistance against British colonialism and Israeli occupation. To this day, the Israeli army conducts routine incursions into Nablus destroying historical houses in its old Ottoman center, but these strong arm tactics have failed to break the resolve of this resilient city.

The copper-domed Greek Orthodox Church on the outskirts of Nablus built on top of the underground chapel housing Jacob’s Well. Steps leading to the well photographed in the 1880s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

Present day Nablus is the second largest urban center in the West Bank. We entered the city from the southeast where streets are lined with shoddily built cement structures, a disappointing introduction to a place of such historical stature. Our first stop was Joseph’s Tomb (Qabr Yusuf), located in Balata, the site of the biblical Shechem and now a crowded residential neighborhood. The significance of the shrine itself is a matter of dispute. For Jewish believers, it is the grave of the biblical Joseph, Jacob’s son, while Moslems believe that it is the burial place of Sheikh Yusuf, a local saint. The tomb, a flashpoint for violence since the 1980s, is off limits to Palestinians. A PA security official manning the checkpoint near the tomb reminded our guide that entry was forbidden. From there we walked to Jacob’s Well (Bir Yaacoub) located in the copper-domed Orthodox church, built at the site of several older churches dating back to 327 AD. The Well of Jacob, known in Christian tradition as the site where Jesus converted a Samaritan woman who then spread the word to her community, is located underneath the church in an ancient chapel. In 1979 a group of settlers tried to take over the chapel claiming that it was a Jewish holy site. The priest who stood up to them, Archmandrite Philoumenos of Cyprus, was brutally hacked to death and thirty years later he was declared a saint. A drink of water from this 40 meter-deep well was most refreshing after a 15 km hike in hot weather.

Standing in front of the alter inside the Greek Orthodox church which sits above Jacob’s Well. A photo from the early 1900s shows a Samaritan woman beside Jacob’s Well. Phot. (L) iPhone (R) N. Schiller Collection, Underwood and Underwood

The old center of Nablus, al Qasaba, contrasts sharply with the outlying areas. It is a maze of narrow alleys bustling with life and activity. The market, reminiscent of Damascus’ souk, houses shops, stalls, and carts that sell local vegetables, spices, sweets, handicrafts, as well as the inevitable Chinese imports. One felicitous item sold here is an arguileh (water pipe) in the shape of an AK-47, a symbol of Palestinian resistance. Unfortunately, the artifact quickly lost its appeal when we found out it was made in China. In the streets near the historic al Kabir mosque, the walls are covered with the portraits of young fighters fiercely peering at passers-by as a reminder that conflict is never far away. In addition to producing martyrs, Nablus is also known for making the best knefeh, a pastry made of goat cheese covered with a layer of semolina and syrup, and the place to have it is al Aqsa, a small hole in the wall which specializes this local delicacy. After our long hike, we rewarded ourselves with a warm gooey portion of knefeh as we watched it being made in large round baking trays across the alley.

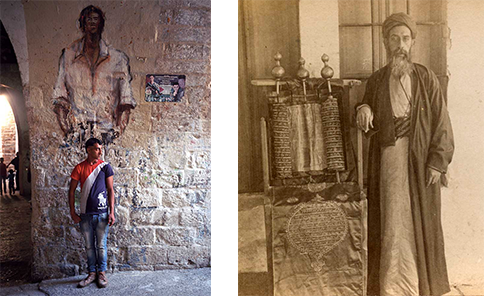

Graffiti in the old section of Nablus glorifying Palestinian resistance. A photograph of the Khan in the old center of Nablus taken in the 1920s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Karl Gröber

Another notable site in Nablus is the Samaritan Quarter, a dark and dilapidated district in the old city. The Samaritans trace their origin to the Israelite tribes that survived the Assyrian conquest and stayed in Palestine during the Babylonian exile. They claim that they practice the purest version of Judaism. However, a rift occurred with the returning Jews in post-exile days and it is still persistent today. Relations with the Palestinians have generally been cordial although there is some suspicion about the Samaritans’ loyalties especially that they hold both Palestinian and Israeli ID and some even have Jordanian travel documents. The Samaritan Quarter was abandoned by its original inhabitants during the first Intifada (1987-1990) and most have resettled on Mount Gerizim.

A Palestinian boy in the old section of Nablus which was once home to the Samaritan community. A Samaritan man stands next to ancient scrolls in Nablus. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Keystone

Also part of historical Nablus is al Yasmeen hotel, where we spent the night. It is a 600-year-old stone building with an inner courtyard and fountain, located in the old city. The hotel has a spectacular view of the central square and its green-domed an Nasr mosque, a well-known landmark, with the mountains in the background. We begrudgingly left Nablus after a half-day visit, with the intention of coming back to explore more of this fascinating multi-faceted city.