Chephren pyramid. Phot. Josef Polleross Collection, Van Leo

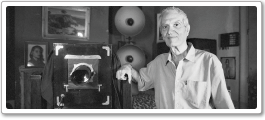

Visiting Van Leo’s studio was like taking a time machine back to the 1950s. However, it was obvious that the studio and its owner had seen better days. The place was dark and run down and Van Leo himself was not in the best of shape. He was 74, but still active as his work kept him alive. His clientele consisted of older people, who had known him at the height of his career, and foreigners who sought him out to have their portraits taken. I asked Van Leo if I could take his portrait and he accepted. He also showed me some of his work and I bought a small print of Chephren, one of the Giza pyramids, which he had taken in 1956. Before leaving, I made an appointment to have my portrait taken. I don’t remember much of the photo session, except that he set up his lights very meticulously and gave me specific instructions on how to pose. I came back a week later to pick up the print.

Van Leo taking a portrait of David and Helen Miles. Phot. Josef Polleross

Josef Polleross, Photographer, Vienna Austria

In 1992, shortly after I switched from collecting postcards to 19th century albumen prints of Egypt, I learned about a studio in downtown Cairo owned by an old Armenian photographer with a collection of retro black and white photos.

When I visited the studio the first time, I felt like I was in a time warp. The furniture and decor were from the 1940s, and the walls were covered with black and white portraits of famous Egyptian entertainers, along those of ordinary people. An elderly man sitting behind a desk in a corner immediately stood up and greeted me in French, but when I responded in Arabic, he switched to English. After exchanging niceties, I realized he was Van Leo, the photographer I had been told about, so I went right to the point and asked if he had any original 19th century photographs from the likes of Bonfils, Zangaki, Arnoux, and Legekian for sale. His expression soured and he questioned my interest in those photographers. I explained that I was collecting 19th century photographs of Egypt, and was told that he may have some. Van Leo seemed slightly offended by my answer and said that he had had some of these photographs in the past, but not anymore. He then went on to berate me on my taste in photographers and their style. Although he acknowledged the historical significance of these photographers, he described their pictures as “lifeless.” He then brought out a stack of photographs similar to those hanging in the studio, and proceeded to give me a lesson on what gave “life” to a picture. At the end of our first encounter, I came away with an entirely new appreciation of photography.

I visited Van Leo a few more times the following months, and each time we would look through his prints as he told me stories about the people in the photos. He had an uncanny ability to remember the slightest detail about every photo shoot. I loved hearing his stories, particularly the ones about the more risqué photographs in his collection which he eventually burned fearing the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in the late 1980s.

Unlike many of my fellow news photographers based in Egypt at the time, I had had no formal training in photography, a career I fell into by chance. Since I was keen to learn the intricacies of the profession, I was more than happy to listen to Van Leo’s stories. I remember trying to take a picture of him sitting behind his desk once, and just before I was about to click the shutter button, he stopped me to give me instructions. “Not like that, you need to prepare the frame and correct the lighting.” That was the only time I ever attempted to take his photograph.

Van Leo offered to sell me some of his prints for which he charged 300 Egyptian Pounds (90 dollars) a piece, a very reasonable sum at the time. At one point I made a list of the images I liked, but I was so fixated on 19th century albumen prints that nothing else seemed to matter. This was one of the many missed opportunities I have had as a collector who is passionate about preserving the past.

Van Leo told me that he didn’t differentiate between clients who were famous or those who walked in off the street. He gave them all equal attention and made them look glamorous, whether they had star quality or not.

My saddest memory of Van Leo was during one of my last visits, when an old friend whom he hadn’t seen in a while dropped in. Van Leo was elated about the visit, but when his friend asked for a reproduction of his passport photo, the artist turned to me exclaiming, “Is this what I have been reduced to? Making reproductions of passport photos!” He then went on a tirade about how people had stopped appreciating quality photographs since the medium had become accessible to amateurs. Today, I have a similar reaction when people ask me about my thoughts on photography, and how it has changed over my own thirty-plus-year career.

Norbert Schiller, Curator, Photorientalist

If anyone would like to share a memory or photos taken by or of Van Leo please contact me at: nschiller@photorientalist.org.