By Norbert Schiller

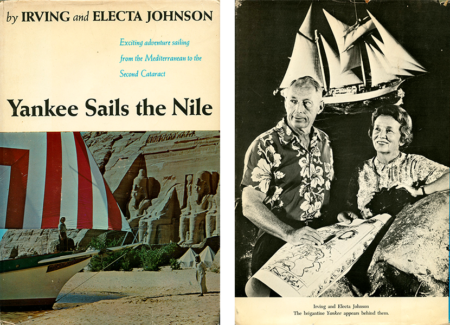

Yankee Sails The Nile describes the four-month journey the Johnsons took up the Nile

Irving and Electa (Exy) Johnson were avid sailors and had owned three boats they called Yankee. After they married in 1932, the couple spent the better part of their life together at sea, sailing to exotic places, writing books, and making films about their adventures. Sailing in their first two boats, a schooner and a brigantine, the pair circumvented the globe seven times in three decades. Their last Yankee, a 50-foot ketch, currently for sale and featured in my photo collection, was built in 1959 by a Dutch designer. The boat was custom-made for the Johnsons for sailing through the inland waterways and rivers of Europe as well as the open oceans. The ketch was built with twin centerboards that could be raised in shallow water and a mast that could easily be lowered to go under obstacles like bridges. It is with this boat that the couple dreamed of sailing up the Nile.

Before arriving to Alexandria the Johnsons where sailing around the Greek island of Rhodes.

National Geographic, which had already featured the Johnsons on previous sailing adventures, sent staff photographer Winfield (Win) Parks to join them for the duration of their journey on the Nile. Besides making the cover story in National Geographic the Johnsons went on to write a book about their trip titled, Yankee Sails The Nile.

As the Johnsons entered Alexandria’s west harbor, they had no clue whether their dream of sailing 1,000 miles up the Nile in their yacht would come to fruition. The reason for their apprehension was that they had not received any concrete response to the numerous letters they had sent to both the Egyptian embassy in Washington and officials in Egypt asking for permission to sail up the Nile. The best they got was an ambiguous letter signed by the minister of culture that promised to look into the matter. Unfortunately, when they arrived in Egypt they learned that the minister who signed the letter had been fired. The other challenge was reaching Nubia in time as the trip took place only months before the construction of Aswan High Dam which would permanently halt river traffic past the first cataract along the Nile.

The Yankee docked alongside a traditional Egyptian Felucca.

After nearly two weeks in Alexandria navigating Egyptian bureaucracy, the Johnsons finally secured the paperwork to sail as far as Cairo thanks to the U.S. Consulate in Alexandria and the Alexandria Yacht Club. On the evening of 31 October 1963, the couple set sail from the port of Alexandria accompanied with a few friends and Ibrahim, a sailor with the Alexandria Yacht Club who acted as their translator and guide until they reached Cairo. For the first leg of what would be nearly a four-month journey, they sailed west along the Egyptian coastline until they reached the mouth of the Rosetta branch of the Nile. Once the Yankee entered the Nile Delta, it was redirected to a canal that ran alongside the river as water levels were too low for safe navigation. After eight days of navigating the canals, overcrowded with Egyptian sailboats known as feluccas, the Yankee finally arrived at the Cairo Yacht Club across from the Shepheard’s Hotel. In the capital, the passengers were joined by Parks, the National Geographic photographer, and their Egyptian friend Ahmed Fahmy, who would prove to be their greatest asset as they sailed south. The Johnsons would later dedicate their book to Fahmy as a testimony of their appreciation. During the voyage, the Johnsons were joined by friends for short periods, but Parks and Fahmy stayed for the entire course.

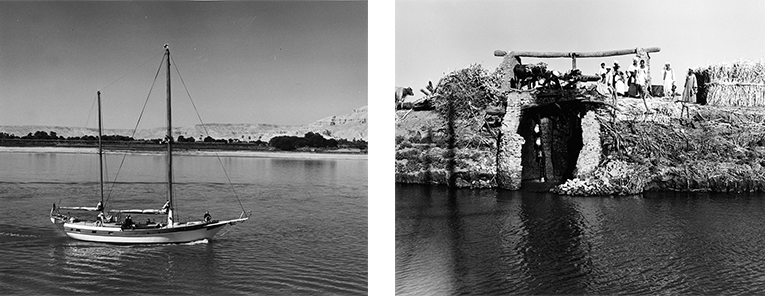

The Yankee motoring upstream against the current on a windless day. Passing a Sanduf lifting water from the Nile to water crops. Phot. Zacher

Exy had stocked up on canned goods and other non-perishable foods before she and her husband arrived in Egypt not knowing if they could depend on the local market for supplies. However, the food she brought was barely touched as Fahmy accompanied Exy to the local markets every time they went ashore to shop for fresh foods which included turkey for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Every evening, when the party tied up on the banks of the Nile, they invariably attracted a small crowd of onlookers. Fahmy, who came from a prominent and well- connected family, would always disembark wherever they stopped to visit people he knew or make the rounds with local officials. By the time he returned to the Yankee, there would be at least one official dinner invitation and a car to take the group on a tour of nearby historical sites.

The Yankee under sail

Wherever the Nile was wide enough, and the wind was blowing from the north against the current, as it often did in Egypt, Irving would cut the engine and continue under sail like the Egyptian sailors in their feluccas plying the Nile waters. For the well-heeled tourist the Nile was a romantic getaway, but for the locals it was a necessity for the transport of goods and services. However, the romance of sailing would cease as soon as the Yankee and its occupants encountered a bridge that needed to be raised or a barrage (dam) where the locks had to be opened. It is on these occasions that Irving’s years of navigating harbors around the globe proved useful as he steered around feluccas, under sail, jockeying into position to pass when the way was clear. Irving also made it a point to assist any felucca driver who was stuck and needed towing into the middle of the river to catch some wind. Surprisingly, very few feluccas used for transporting goods had motors on them.

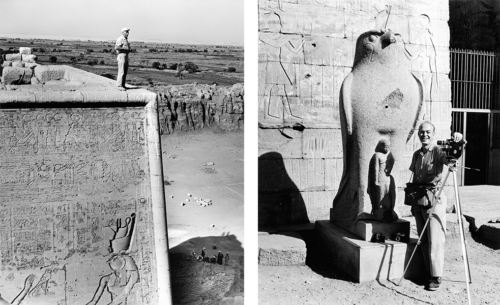

Irving Johnson (L) and Ted Zacher at Edfu Temple

During the journey south, the travelers stopped at all the popular tourist sites as well as the less famous monuments such as the pyramid at Harawa near Beni Suef and the ruins and tombs of Tel el Amara outside Assiut. Shortly after the boat left Cairo, Exy wanted to visit a typical village along the Nile, so the group pulled up to a random village and went ashore surprising the locals who couldn’t understand why these western visitors had descended on their tiny hamlet. Being on the Yankee gave the Johnsons and their friends the freedom to stop anywhere they pleased and gave them access to remote places that were rarely visited by outsiders.

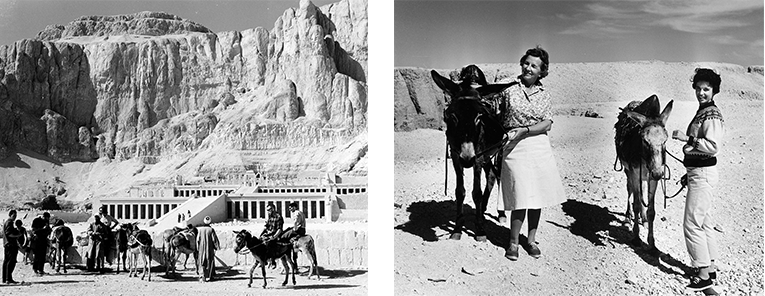

Visiting the Temple of Hatshepsut (L). Donna Grosvenor (R) and Exy riding donkeys in the Valley of the Kings. Phot. Zacher

After six weeks of sailing, the group finally made it to Luxor where they were given a berth right in front of the famous Winter Palace Hotel. There, The Nelsons, who had been on the trip since Alexandria, left and were replaced by Ted Zacher, a good friend of the Johnsons who had sailed with them on previous adventures. Zacher, a filmmaker, brought along movie equipment to record the journey. When they were not visiting Pharaonic sites on both banks of the Nile, the Johnsons entertained a steady stream of visitors aboard the Yankee ranging from missionaries to archeologist. The sailboat had become another tourist attraction of sorts for passersby who just wanted to take a peek at the notorious vessel with eccentric owners.

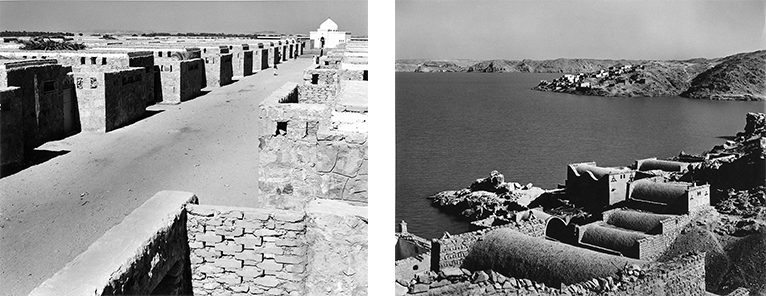

The village of New Debot near Kom Ombo that will house some of the 100,000 displaced Nubians. A traditional Nubian village that had to be evacuated with the building of High Dam. Phot. Zacher

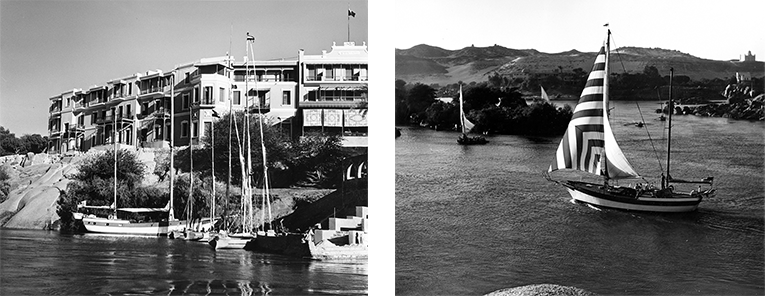

On the next leg to Aswan, the Yankee ran aground a few a times as the flow of the Nile had been altered to accommodate the construction of the High Dam further upstream. From there until they passed the first cataract, the depth of the river would fluctuate and often hamper the Yankee’s progress. Continuing south, the group stopped at Kom Ombo to visit its famous temple, and from there they got their first glimpse of the recently built village of New Debod meant to accommodate some of the 100,000 Nubians whose ancestral homes had been flooded by the construction of dam. The ancient Egyptian Temple of Debod, dedicated to the sun god Isis, that also shared the same name as the village, was later given to Spain as a gift to show gratitude to the country for its contribution to saving Abu Simbel. The Debod temple would eventually be reconstructed in a Madrid park. Even though the Yankee’s occupants were impressed with the organization and planning behind the resettlement program, they were disheartened by the layout of the new village. Parks described the new settlement as “a bowling alley” because it had been built in straight lines, a far cry from the charming sinuous villages it was meant to replace. At Aswan, the travelers docked below the Old Cataract Hotel where they resumed their social life including celebrating Christmas with a turkey aboard the Yankee. In Aswan they visited the ancient sites and were given a tour to the High Dam to see the construction work at close range.

The Yankee docked below the Old Cataract hotel in Aswan. The Yankee sailing in the waters around Aswan. Phot. Zacher

The Yankee made it to Nubia about five months before the cut-off date of May 14, when no boat would ever be allowed to make the journey south as sailors had done since the dawn of time. After passing through a series of five locks, the boat entered Nubia where the passengers found once lively villages turned into ghost towns. Exy described what she saw as follows:

There were no shadufs raising water from the Nile, no green of cultivation with the robed figures following the primitive plows, no black garbed women with water jars on their heads, no screaming children, not even feluccas. If we had not known why Nubia was deserted we might actually have been afraid of this strange silent landscape, like what one imagines on an unknown planet.

After entering the floodplain that would become Lake Nasser, the Johnsons stopped at Beshir, one of the first abandoned villages they encountered and got off the boat to investigate. The contrast with the new settlements was flagrant to the visitors as Exy noted in the memoir.

An empty Nubian village

Beshir was built on a rocky shore and everything was irregular—the angles of the houses, the paths that had to wind around the big rock instead of going strait, the levels of the different buildings, the natural steps worn among the rocks where people had gone up and down, the contours of the rocks, the light they caught, the color they revealed. It was the irregularity of human beings, the adjustments of their living to the natural setting. What could be more different from the resettlement villages we had seem near Kom Ombo, where everything was laid out in impersonal strait lines, right angles and uniform repetition.

Wim Parks from National Geographic is seen photographing the last celebration at a saints tomb before both the holy man and the villagers will be relocated downstream (L). The other image show Parks photographing a village from the Yankee that has chests and people waiting to be picked up by a barge. Phot. Zacher

As the Yankee continued southward, it passed villages where locals sat near chests and boxes piled high beside the shoreline waiting for the government barge to move them out. In one of the hamlets, the group witnessed a celebration taking place for the last time at the tomb of a local saint. After this event, the entire village was to be relocated downstream where a new tomb would be constructed for the sheikh. The traveler also met archeologists working frantically at different sites to gather as much information before the rising waters swallowed up their digs. For years, there had been discussions about which archaeological sites to save and which ones to sacrifice to the grand project of the dam. As a result, museums and universities from around the world sent droves of archeologists to Egypt to do as much research as possible about Nubia before the entire area was submerged under water.

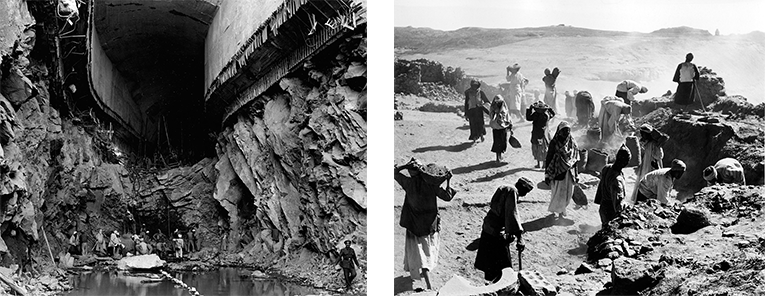

Egyptians work around the clock on the construction of High Dam (L). At the same time other Egyptian laborers work with archaeologists from around the world to try and gather as much information about Nubia before the entire area is submerged in water. Phot. Ted Zacher

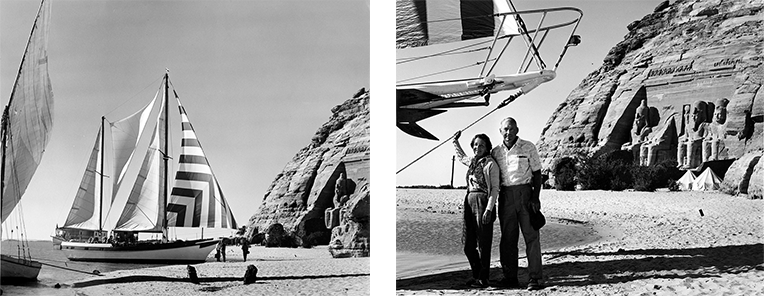

The climax of the group’s venture into Nubia was arriving to the temple of Abu Simbel, dedicated to the sun god Ra-Horakhty and built by Ramses II in 1265 BC. After considering different options on how best to preserve the temple, the world community and Egyptian authorities finally decided that it would be cut into giant blocks of rock weighing approximately 30 tons each and rebuilt on higher ground away from the floodplain. Shortly after the Yankee left, the relocation work began.

Exy and Irving’s dream of sailing their 50 foot yacht Yankee 1000 mile up the Nile climaxed when they made it to the temple of Abu Simbel at the southern most part of Egypt. From there they would carry on to the Sudanese frontier town of Wadi Halfa before retracing their steps back down the Nile. Phot. Zacher

From Abu Simbel, the Johnsons sailed up to the Sudanese frontier town of Wadi Halfa, just below the second cataract. There, they visited a number of historic sites including the Kumma fort located at the southern end of the second cataract where the Nile narrows and the water can be seen rushing over the rocks. In Wadi Halfa the Johnsons were joined by their friends Gil Grosvenor of National Geographic and his wife Donna.

The Yankee sailing from Abu Simbel to the Sudanese frontier town of Wadi Halfa and the second Cataract. Phot. Zacher

On the return journey, the Yankee, now with seven passengers onboard, stopped one last time at Abu Simbel. The group then continued north visiting some new sites including the Roman Fort of Kasr Ibrahim in Nubia where Irving fell and cut his head when the ruins he was standing on partially collapsed. Luckily, archeologist working on the site knew of a small hospital that was still operating and was only a short boat ride away. After getting sixteen stitches in his head, Irving was ready to continue the journey. In Aswan the party met with Begum Om Habibeh, the wife of the late Aga Khan III, who was wintering at her house in Aswan located on an island in the Nile.

From Aswan the group continued downstream to Luxor where the Grosvenors and Ted Zacher disembarked while two other friends, Gould Eddy and Allen O’Brian, took their place. The new passengers were both avid sailors who accompanied the Johnsons for the next six weeks until they reached the Greek Island of Rhodes. Traveling slowly back down the Nile, the party stopped once again in Assiut but this time they were taken by car overland 120 miles to visit the Kharga Oasis in the middle of the Western Desert.

When the Yankee arrived in Cairo, the Johnsons said their goodbyes to Parks and Fahmy and continued along the Ismailia canal just north of Cairo all the way to the Suez Canal. From there, they sailed north towards Port Said and then crossed the Mediterranean to the Greek Island of Rhodes. The Yankee’s historic voyage marked the last time a boat sailed all the way up the Nile to the second cataract. A few months after the vessel and its owners left Egypt, construction on the Aswan High Dam began changing history forever. That is what makes the photos in this collection so remarkable.

Note– The photos featured in this story were taken by Exy Johnson and some of her and Irving’s friends who joined the Yankee’s Nile expedition. Many of the photos were published in Yankee Sails The Nile. National Geographic’s Win Parks did not take any of the images included in this feature.

Thanks again for the article, I’ve made some internet research and found this on the NatGeo archive

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cZT1IHBzkaY

Thanks for this great post, for the great photos, and for keeping these memories alive! There is a little more info on the youtube film linked above at National Geo: https://nglibrary.ngs.org/public_home/filmpreservationblog/yankee-sails-the-nile-1964. The reason there is no audio is that Irving traveled and showed this film while providing live narration. I’m not sure if the audio was ever captured. If it was, that would be quite a find. As it stands, even this film was only recently unearthed at in the vast National Geo archives. Most of the Johnson’s papers, photos, logbooks, etc. are place at Mystic Seaport Museum (https://research.mysticseaport.org/coll/coll240/). They used to have a nice story map with photos but I don’t see it posted at present. -Karl Johnson

Dear Norbert,

It has been now probably over 20 years that we did not communicate. My name is Alexandre Starker and we met in Cairo (where I reside) in around 1999/2000. I was very happy to discover your photorientalist.org site – not only because of the many good quality vintage pictures (Suez Canal and King Farouk) but also for the Johnson family Yanke trip south to Abu Simbel album. Together with some friends of the Cairo Yacht Club – particularly Cherif Mazhar – I had the pleasure to be involved in that cruise. As mentioned by Mr. Karl Johnson, going through the interesting Mystic Seaport Museum on the US East Coast, I was able to purchase nice photos as well as a film cassette of that trip. Hope to hear from you soon. All my best thoughts. Alexandre Starker