by Norbert Schiller

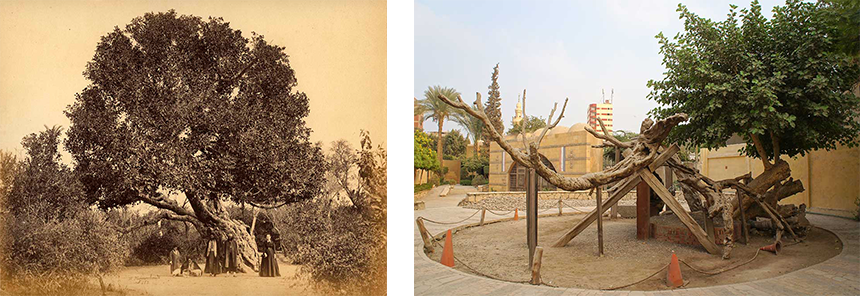

Shortly after the July 2013 military coup that overthrew Egypt’s first democratically-elected president Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Moslem Brotherhood, the Virgin’s Tree mysteriously collapsed. A rumor quickly circulated that this sacred relic had been cut down by thugs seeking revenge for the Copts’ support of Abdel-Fattah el Sisi’s new government. The Coptic Church immediately denied the rumor and issued a statement saying that the tree had blown down during strong winds.

Both photographs taken in November 2016 show the two remaining branches which are now forming a new tree. Phot. Shen Shangyun

A colleague recently visited the site seeking to determine the truth behind the tree’s demise. He spoke to a number of people including the caretaker who, after giving him a twig from the tree as “baraka” or good luck, told him that the tree had fallen down because underground water had saturated the soil that was holding the roots in place. To make things worse, the tree fell onto the wall built around the area and, because the huge canopy was blocking the sidewalk, authorities had to cut it. Only two small branches have survived this disaster, and they are now forming a new tree.

While working on the Holy Family book, I traveled throughout the country to all the places that allegedly were visited by the Holy Family. Some of the locations are well known like the oasis of Wadi Natrun in Egypt’s Western Desert or Babylon, south of Cairo. Others are more obscure like Jabal al Tayr, Mountain of the Birds, across the Nile from Menya, or al Quasya overlooking the Nile in Upper Egypt. Those sites are marked by monasteries and churches, fresh water wells connected with Jesus, and a half dozen trees that folklore says gave shade to the Holy Family as they passed, the most famous of which is the Virgin’s Tree at Matariya.

The 2013 incident was not the first disaster in the sacred tree’s long history. Although tradition claims that the tree is 2,000 years old, the original most likely has long vanished and been replaced several times. In G. Ebers’s 1878 book, Picturesque Egypt, the author quotes a 17th century traveler who describes a much earlier death of the Holy Tree.

“It is no doubt of great age, but we can only regard it as the successor of an older tree which was already dead when (G. M.) Vansleb visited Egypt in 1672. This trustworthy traveller was told by monks in Cairo that the Virgin’s tree had died of old age in 1656, and they showed him its remains, which were preserved as a most precious relic.”

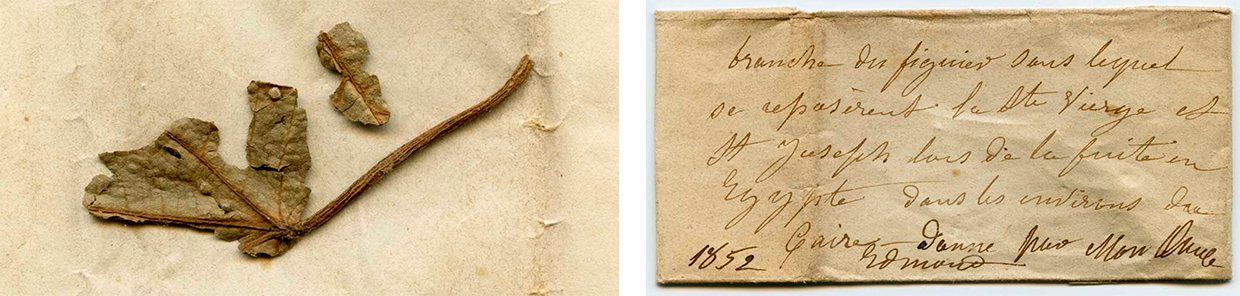

A leaf that was broken off from the Virgin’s Tree by a Belgium pilgrim in 1852(L). The leaf was wrapped in this paper which had a note in French saying the following: “A branch from the fig tree around Cairo under which rested the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph during their flight to Egypt.” Norbert Schiller Collection

Ironically, much of the damage to this relic has been inflicted by pilgrims who break off branches and peel off pieces of the bark for keepsakes, or, even worse, carve their names onto the trunk. Today, there are several dead tree trunks at the site, and some of them carry the names of some of Napoleon’s soldiers. In the late nineteenth century travel book, A Handbook for Travellers in Egypt, the writer bemoans visitors’ selfish and irresponsible behavior.

“It is a splendid old tree, still showing signs of life, but terribly mauled alike by the devout and the profane, who respectively have forgotten their piety and their skepticism in the egotistical eagerness to carry away and to leave a record of their visit. The present proprietor, a Copt, fearing lest their united efforts should result in the total disappearance and destruction of the tree, has put a fence round it, which, while it prevents the ruthless tearing off of twigs and branches, affords those who are anxious to commemorate their visit a smooth and even surface on which, with the help of a knife obligingly kept in readiness by the gardener, they may make their mark.”

In addition to being the location of the Virgin’s Tree, Matariya is well-known for its once flourishing gardens, famous for their balsam trees. Balsam oil was highly coveted and, between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries, it wasn’t uncommon for the rulers of Egypt to attend its prestigious harvest. The oil was used for medicinal purposes and was a key ingredient in liturgical oils for the Coptic Church and other churches in Middle East and Europe.

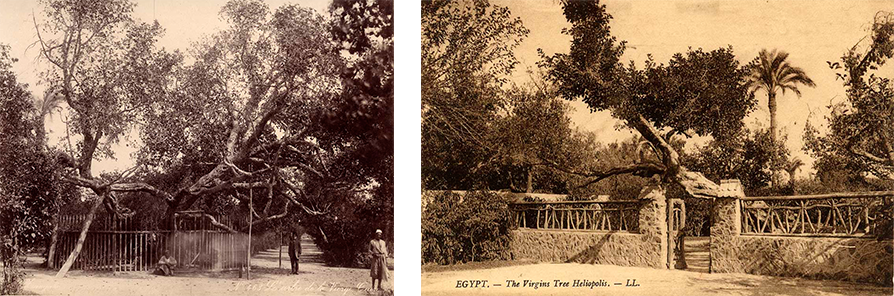

In the 1880s a fence surrounded the Virgin’s Tree (L). In the early 1900s a wall was build to protect the tree. Phot. (left) Zangaki, Norbert Schiller Collection

It is unclear exactly what type of tree allegedly sheltered the Holy Family at Mataryia. The earliest records mention a balsam tree, but there are also travelers who speak of a fig or palm tree. What is known is that every tree that has been planted in this spot since 1672 is a sycamore, considered sacred in pharaonic times. One of the earliest accounts about the tree comes from Venetian traveler Mariano Sanuto’s 1321 travelogue, Secrets For True Crusaders. In his book, Sanuto says a palm tree stood at this site.

“Near Cairo is an exceedingly ancient palm-tree, which bowed itself to the Blessed Virgin Mary that she might gather dates from it, and then raised itself up again. When the heathens saw this they cut it down, but it joined itself together again in the following night and stood upright again. The marks of the cutting may be seen to this day…This garden can only be watered from one single fount, wherein the Blessed Virgin is said to have washed the boy Jesus’s swaddling clothes. At the season of Epiphany both Christians and Saracens assemble at the fount, and wash themselves therein out of devotion. Another miracle there is that the oxen that draw the aforesaid water would between mid-day on Saturday until the same hour on Sunday, not though you were to skin them alive.”

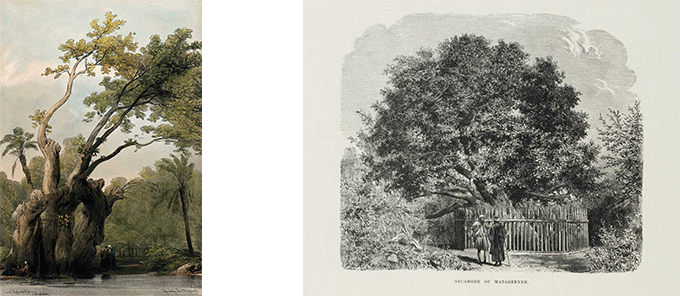

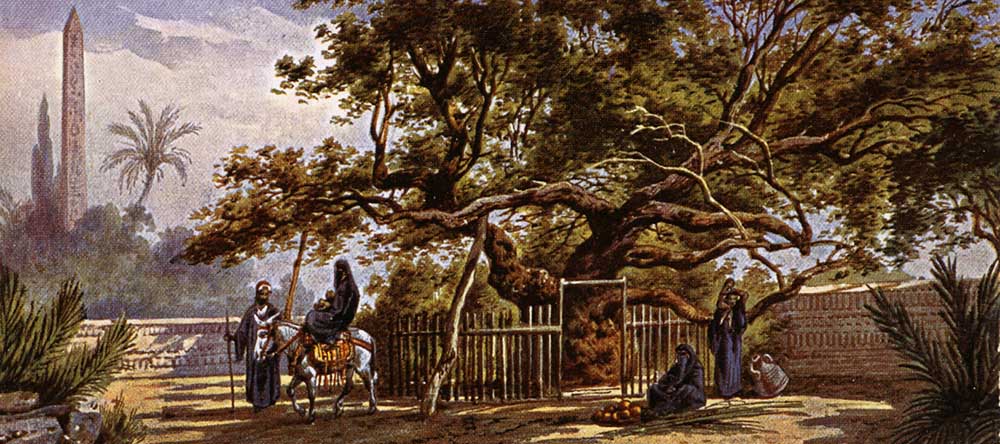

A color lithograph of the Virgin’s Tree by David Roberts from 1832 (L). A wood etching found in G. Ebers’s 1878 book Picturesque Egypt.

Like many other villages near Cairo which once were distinct rural settings surrounded by gardens and fields, Matariya has been swallowed up by the sprawling capital. This once picturesque hamlet now looks like any other overpopulated Cairo suburb, with alleyways strewn with garbage, haphazard construction, concrete apartment blocks and fly-overs dominating the skyline. In the middle of the chaos the Virgin’s Tree, or what remains of it, still stands in a small walled-in enclave, a desperate attempt to preserve the tatters of a glorious past. In his 1845 travel book Egypt and Nubia James Augustus St John describes Matariya, and the tree, at their prime.

“Sometime before arriving in Matarea, we turned into a citron grove on the right hand of the road, to behold that the venerable sycamore, in whose shade the Virgin, with the infant Christ, is said to have reposed during the flight into Egypt. In all respects this grove was an agreeable retreat. The spaces between the trees, roofed by thick canopy of verdure, completely excluded the rays of the sun, while a cool breeze circulated through them freely. Other kinds of fruit-trees, besides the citron, rose here and there in the grove, and presented, in their unpruned luxuriances, an aspect of much beauty. Birds of agreeable note, or gay plumage, flitted to and fro, or perched upon the branches; otherwise, the silence and stillness would have been complete, and might have tempted me to remain there for hours, delighting my imagination with reminiscences of the Arabian Nights, whose heroes and heroines are often represented reposing in such places…The Tree of the Madonna, as it is denominated, even by the Mohammedans, consists of a vast trunk, the upper part of which having been blown down by storms or shattered by lightening, young branches have sprung forth from the top, and extending their arms on all sides, still afford a broad and agreeable shade. Its shape is remarkable: flat on both sides, like a wall, but with an irregular surface, it leans considerably, forming a kind of natural penthouse.”

One of the earliest photographs of the Virgin’s Tree taken in the 1860s alongside a recent photograph from November 2016. Phot. (left) W. Hammerschmitd, Norbert Schiller Collection. Phot.(right) Shen Shangyun

It is no secret that the drainage in Cairo and its surroundings is inadequate at best. After a light rainfall, the city is paralyzed as its main thoroughfares and back streets become flooded. The rising water table has also threatened many archeological sites including the Sphinx, where underground water had to be diverted. Therefore, it is most plausible that ground water is the culprit behind the most recent demise of the Virgin’s Tree and not religious tensions as some may want to believe.

Throughout the ages, the Holy Tree has had to contend with its own lifespan, tourist infractions, and spreading city limits; now it faces a new environmental hazard. If the tree, or whichever version of it, is to continue to exist and play its role in Coptic and Egyptian lore, more serious efforts will need to be exerted to protect it from the growing number of threats that it is facing.

Nice photos and text but how did the tree look like in the year 2000 when we worked on the book Be Thou There?

Your photos compare 19th century photos and illustrations with photos from 2015 and 2016. But what about photos between 1900 and 2015?

Lovely story and a nice piece of historical research. One can only hope that the Virgin’s tree survives its latest challenge!

Your collection is unique and the way it is presented deserves to be seen by many people. In Medieval days European pilgrims called this location ‘the good garden’ and compared this to Paradise because of the balsam plants growing here. Today little is left of this once paradise like location. I hope your exhibition will contribute to the preservation of this unique location. I was pleased to dedicate a newsletter of Arab-West Report to your exhibition.

Cor Hendriks – Magi: de wijzen uit het Oosten (2): Jezus in Egypte | Rob Scholte Museum

[…] https://www.etltravel.com/mary-tree-cairo/virgin-mary-tree-matareyya-cairo/. Meer over de boom op http://www.photorientalist.org/exhibitions/egypts-virgin-tree-story-survival/article/. Een bespreking van het Evangelie is te vinden op […]

The photo which is linked, in the website box below, shows the tree in 1912 or 13 at a time when my grandfather, H.T.Sutters, was an electrical engineer, working for an English contractor, installing electrical systems into Abbassia Barracks near Cairo. The photograph may be copied and added to this interesting record. If there is any problem with doing that, please contact me via email.

Homepage

… [Trackback]

[…] Informations on that Topic: photorientalist.org/exhibitions/egypts-virgin-tree-story-survival/article/ […]