By Zina Hemady

The last leg of the journey consisted more of visits to tourist sites than hiking through the pastoral tranquility of rural Palestine. Nevertheless, the experience was still fascinating revealing once secluded monasteries carved into the walls of deep river valleys, a Moslem shrine dedicated to Moses, and a canyon rich in springs, native plants, and wildlife. Although these sites can temporarily distract visitors from the conflict gripping these lands, reality looms large when approaching Bethlehem, the mythical city of angels and shepherds, now defaced by a gruesome cement barrier and strangled by mushrooming settlements.

Approaching Saint George of Koziba monastery in Wadi Qelt. A similar view of the valley from 1904. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, unknown photographer.

The most rewarding hike after Jericho was the trek through Wadi Qelt, a water-fed canyon with high cliffs stretching over 40 km between Jerusalem and Jericho. While it is possible to walk the entire distance over two days, we only hiked the last 9 km stretch which is the most popular. That part of the trail includes a number of historical landmarks such as the Herodian bridge that once held up an aqueduct from the same era and Saint George of Koziba, which started as a place of spiritual retreat in the 3rd century before becoming a full fledged monastery two centuries later. However, it is the wadi’s layered upright limestone cliffs, springs, pools, vegetation and wild animals which are its main attraction. Walking along a modern water channel, we spotted the elusive rock hyrax, a mammal related to elephants but that resembles a guinea pig, and various species of birds including larks, swallows, and the bulbul renowned for its sweet song. At the end of the one hour walk, we ran into a group of Palestinian youth from Jerusalem who had also hiked to the monastery. While nature outings until recently had only attracted tourists and settlers, they have become popular among the locals seeking a break from their politically charged lives. One of the first avid hikers in the West Bank is activist lawyer and author Raja Shehadeh who wrote Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape. In his book, Shehadeh who began hiking in the late 1970s, describes the drastic changes he has witnessed in his walks around Ramallah, the Jerusalem wilderness and the ravines of the Dead Sea as a result of Israel’s relentless land grabs. In a plea to his readers, the author describes what it feels like to face the constant fear of loss.

“How unaware are many trekkers around the world of what a luxury it is to be able to walk in the land they love without anger, fear, or insecurity, just to be able to walk without political arguments running obsessively through their heads, without fear of losing what they’ve come to love, without the anxiety that they will deprived of the right to enjoy it. Simply to walk and savor what nature has to offer, as I was once able to do.”

(Palestinian Walks, p. 33.)

A closeup of the Nabi Moussa shrine with its multiple domes alongside a photo of the shrine from the 1920s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Karl Gröber

The next stop was Nabi Moussa, a mosque built by the Mamluks in the 13th century. The large walled complex with its cluster of white domes, stands in sharp contrast with the bare desert landscape south of Jerusalem. According to Moslem tradition, the site is the burial place of Moses as revealed in a dream to Salaheddine, the hero who defeated the Crusaders and recaptured Jerusalem and Palestine. The prophet’s bones are said to be preserved in a tomb covered in a green cloth inside the complex. Due to its significance to the Moslem faith, this shrine or maqam became the site of a yearly pilgrimage starting in the 13th century. The festival took place in the period preceding Orthodox Easter, when thousands of pilgrims marched for 7 days from Jerusalem to Nabi Moussa. The celebration was banned by the British in the 1930s, then by the Jordanians after they took control of the West Bank in 1948, allegedly for fear that such religious gatherings would turn into political protests. Under Israeli occupation, a more subdued version of the festival was occasionally allowed to take place, but the event has largely been suspended.

Walking East through the Jerusalem wilderness towards the Monastery of Mar Saba. An early 1920s photograph of the same area. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Karl Gröber

Under the merciless midday sun, we crossed the desert heading southwest to the monastery of Mar Saba, an equally vast spiritual complex belonging to the Christian Orthodox sect. The monastery, which has not changed much since it was first captured by photographers in the 19th century, is either built on or carved into the cliffs of the Kidron Valley or Wadi el Nar. Founded by Saint Sabas in the 5th century, the monastery continued to grow and prosper until it was destroyed by the Persians almost two hundred years later. Like many of Palestine’s Christian places of worship, Mar Saba still houses the skulls of hundreds of monks killed during the Persian invasions. The monastery was subsequently rebuilt and continued to flourish under Abbasid, Fatimid, and Crusader rule, but then declined until the Russians renovated it in the 19th century. As impressive as it from across the valley, Mar Saba loses some of its appeal at close range due to the stench rising from the Kidron River below. The once crystalline stream has become a torrent of waste water carrying untreated sewage from Jerusalem to the Dead Sea and is gravely endangering the region’s delicate ecosystem. Another disappointment is that only men are allowed to tour the monastery and visit the church, the chapel, and the hermits’ caves. Female visitors can walk up to the 17th century Women’s Tower which offers a limited view of the complex’s interior.

A present-day photo of the monastery of Mar Saba alongside a 1880s image from a similar angle. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

The rest of the trip consisted of visits to Biblical sites which are typical destinations for the tens of thousands of Christian pilgrims who flock to the Holy Land every year. The locals lament that most of the tourists are transported by bus from Jerusalem by Israeli tour agencies for a lightning tour of the sites after which they are whisked back to Israel. The visitors are discouraged from meeting Arabs or frequenting their restaurants and shops, depriving business owners from much needed tourism income. In addition, the Israeli-built barrier, which Israel claims is a security necessity but Palestinians consider a ploy to annex more of their land, has severed the ancient connection between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, the metropolis on which the smaller city depended for education, social and medical services, employment, and cultural life. Finally, the expanding Israeli settlements, which currently number about 20, have reduced Palestinian-controlled land to 13 percent of the total area around Bethlehem. All these factors have transformed the legendary city into a ghetto with 35 percent of its inhabitant living under the poverty line and an unemployment rate of 25 percent.

The view from the Greek Orthodox site of Shepherds’ Field shows an Israeli settlement and Bethlehem in the background. A photo of Shepherds’ Field in the 1880s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

It is easy to get swept up by Biblical lore when touring the sites connected with Jesus’s birth in spite of the tacky commercialization of these sacred locations. Shepherds’ Field, which buzzes with tour groups from all over the world, is where the angel allegedly announced Jesus’s birth to the shepherds. As is common with Biblical tales, there are different locations to commemorate this event. The Roman Catholic site includes a 1954 Franciscan church built in the shape of a shepherd’s tent, while the Greek Orthodox church is located in a small valley with ancient olive trees. The Byzantine church dates back to the 5th century whereas the cave underneath it was marked as a sacred site in 325 by Constantine the Great’s mother Saint Helena when she visited the Holy Land. The cave is believed to contain the tombs of three of the New Testament shepherds. Across the fields to the West toward Bethlehem are hills which were virgin landscape in the 19th century, but are now barely recognizable as they have been overtaken by settlements.

Cars parked in Manger Square during Orthodox Palm Sunday service. A colorized photochrome of Manger Square taken in the 1880s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

After spending the night at a Bedouin-style camp for tourists about 10 km southeast of Shepherds’ Field, we walked along the main road back up to Beit Sahour. As we approached the town, we heard the sounds of bagpipes which, as it turned out, came from the scouts’ marching band performing during the Orthodox Palm Sunday celebrations. Families, dressed in their Sunday best, gathered in the town center to cheer the youth as they wound their way through Beit Sahour’s narrow streets ending at the church. From there, we marched onto Bethlehem, where no visit is complete without a tour of Manger Square and the Church of the Nativity. Built by Constantine and Helena in 326, the church was severely damaged during the 6th century Samaritan revolt, but was rebuilt by Justinian and later expanded especially under the Crusaders. Entering through the Door of Humility, a tiny opening resized twice to prevent attacks by invaders on horseback, we accessed the huge complex which includes a modern basilica, several chapels, cloisters, and monasteries representing the Catholic, Orthodox, and Armenian sects. We gradually made our way to the Grotto of the Nativity, where worshippers, seeking a special blessing on this religious occasion, pushed and shoved to touch the 14-pointed star set in marble believed to mark the exact birthplace of Jesus. From there we visited Saint Catherine’s Church underneath which is a cave with tombs and skulls connected to the New Testament Massacre of the Innocents, when King Herod ordered the massacre of infant boys shortly after Jesus’s birth.

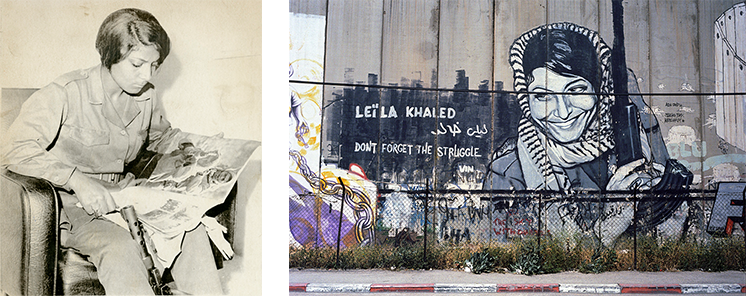

A 1970 picture of Leila Khaled, the first woman hijacker who has become an icon for many in Palestine, next to a graffiti based on a portrait taken of her by Pulitzer prize winning AP photographer Eddie Adams. Phot. (L) N. Schiller Collection, AP Wirephoto, (R) Norbert Schiller

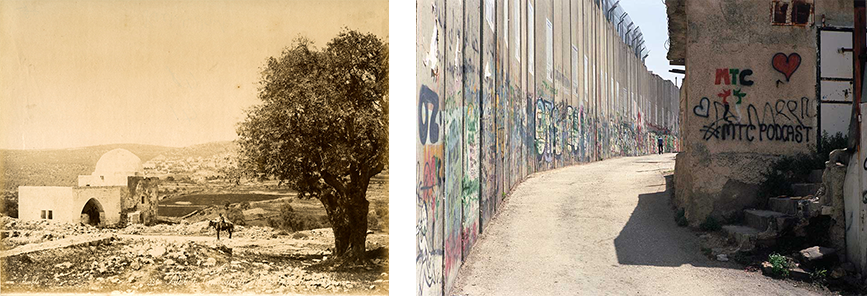

Our last day in Bethlehem was spent touring the area near the wall to get a sense of how the barrier has affected the city’s neighborhoods and residents. As we walked along the 9-meter-high structure, we admired the graffiti by British street artist Banksy and others exposing the cruelty of the occupation. Although the public art, which has had a great deal of international acclaim, has drawn attention to the plight of Palestinians, it has also become controversial as many locals feel that it has sensationalized their tragedy. A perfect example of the devastating effect of Israel’s wall is the fate of the Anastas family whose home ended up being almost entirely engulfed by the barrier. Unfortunately for the Anastases, their house was located across the street from Rachel’s Tomb, the alleged burial place of the wife of the Old Testament’s Prophet Jacob. In their endeavor to take control over the site, which is of religious significance to Jews, Christians, and Moslems, Israeli authorities created a curve in the wall that devoured the family’s property and livelihood. When we reached the “End of the World” Street where the home is located, we met Daniel Anasta who was futilely sitting in his parents’ empty souvenir shop on the ground floor of their villa. We could hear the tourists milling around on the other side of the barrier, but none were able to cross over to admire the olive wood figurines and traditional Palestinian embroidery that the shop had to offer. Daniel, 19, attended Bethlehem University for a year but then dropped out and now hopes to go to school in Germany. Once he leaves, he isn’t sure if he will ever come back to his native Bethlehem.

Rachel’s Tomb just outside of Bethlehem as it was captured in the nineteenth century. Isarel’s barrier has strategically placed the tomb on the Israeli-occupied side and in the process cut off the flow of tourists and tourism revenues from the Palestinian areas . Phot. (L) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils, (R) Norbert Schiller

After decades of occupation and with the chances of a solution that does justice to their cause dwindling every day, it is easy to understand why many Palestinians would want to give up and seek a future elsewhere. However, even in the diaspora, visions of Palestine with its rolling hills, olive groves, and orange orchards still haunt those who once called this land home. Grandparents who lost everything but their memories, continue to share their stories with foreign born grandchildren who in turn carry the longing in their hearts. For those who stayed, life is a daily ordeal, but there is consolation in the fact that they remain close to their ancestral lands striving to maintain their identify and heritage despite a fierce campaign to erase them.