By Norbert Schiller

Since antiquity, there have been numerous attempts to dig a navigable canal connecting the Nile river in Egypt with the Red Sea. Even though there are rumors of successful excavations, no canal ever survived the wrath of the desert until the mid-19th century when the Suez isthmus was split, carving a seaway connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea.

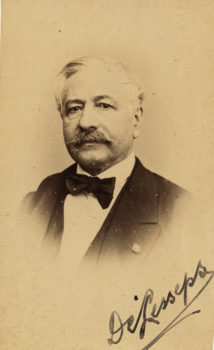

Ferdinand de Lesseps, the architect of the Suez Canal. Phot. CH. Reutlinger

During Mohammed Ali’s rein (1801–1849), a group of influential engineers and intellectuals in Europe, including France’s Henri de Saint-Simon, formed a political and economic ideological front called the Saint-Simonians that looked at what science and technology could do for the betterment of the working-class. However, they were well aware that peace and stability were key factors for prosperity. One of their theories to bring stability was to shorten the distance it took to travel between countries. For example, they sought to shorten the route to the east, which at that time was reached by sailing around the horn of Africa. One of their ideas was to transit Egypt in some capacity. However, even though they all agreed on Egypt as the transit point, there were disagreements on how to implement such a momentous project. One proposal was to expand on existing canals along the Nile and then dig one from Cairo, similar to the canal dug in antiquity, from the Nile to the Red Sea. Another idea was to dig a canal directly through the isthmus at the eastern end of Lake Manzala to the Port of Suez. Still a third suggestion was to skip canals all together and build a railroad network for freight and passenger transport from the port of Alexandria to the port of Suez. While the different camps debated how to achieve the same goal, Ferdinand de Lesseps, a French career diplomat stationed in Egypt in the 1930s and aligned with the Saint-Simonians to some extent, was firm in his belief that a canal cutting through the isthmus of Suez was the only solution.

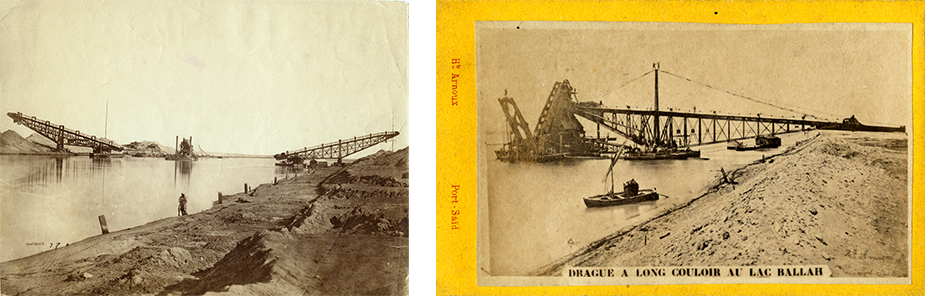

Early photographs of dredging in the Suez Canal from 1868-69. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Hippolyte Arnoux

The relationship between Ferdinand de Lesseps and the viceroy of Egypt, Mohammed Ali, was relatively close. It dated back to Ferdinand’s father, Mathieu De Lesseps, who had been sent to the country during the time of Napoleon Bonaparte I to act as an intermediary between the French and the Egyptian army. At the time, Mohammed Ali was a young officer and struck up a relationship with the elder De Lesseps. When Ferdinand was posted council general in Egypt, he received special treatment from Mohammed Ali and forged a good relationship with his son Said.

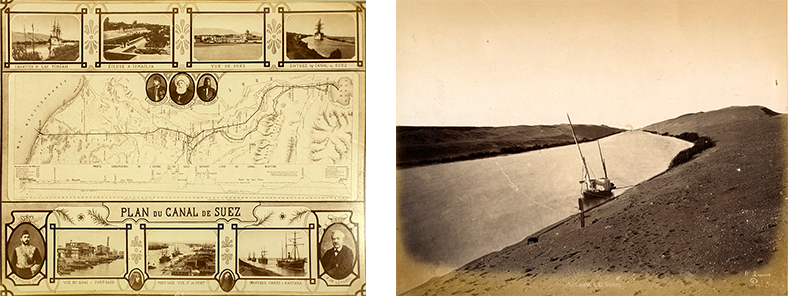

A map of the Suez Canal linking the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. The small sailboat was used by photographers Arnoux and Zangaki brothers to travel along the Suez Canal. The boat was equipped with a small darkroom to process glass plate negatives. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Arnoux

Mohammed Ali’s obsession was to transform Egypt from being an underdeveloped country to a modern state on par with Europe. In order to achieve this goal, he hired foreign advisers and gave concession to foreign companies to upgrade the infrastructure and irrigation systems which would improve the yield of cash crops such as cotton. He also sent many students, including his son Said, abroad to France and Britain in the hopes that they would return ready to implement his dream. One of his aspirations was that Egypt would become the major transit point to move people and goods from Europe to the far east replacing the much longer route around the Cape of Good Hope, but as there was still much debate on how best to proceed with this plan it did not materialize during his lifetime. Nevertheless, one more humble initiative did take off the ground. In the 1830s, an English lieutenant stationed in Egypt named Thomas Waghorn found a way to cut the time it took for mail to travel east by sending it to Alexandria from where it was loaded onto boats sailing up the Nile to Cairo and then transported to Suez by donkey or camel. In Suez the mail was then put on another steamer.

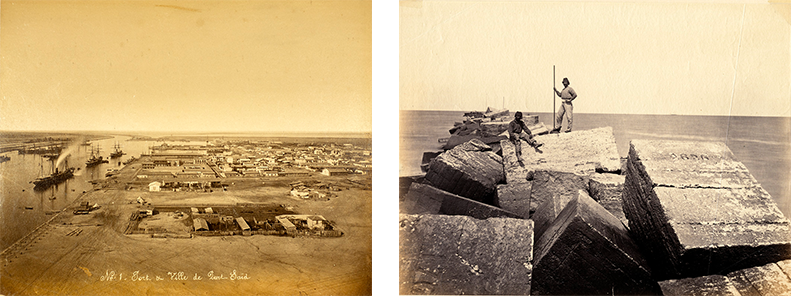

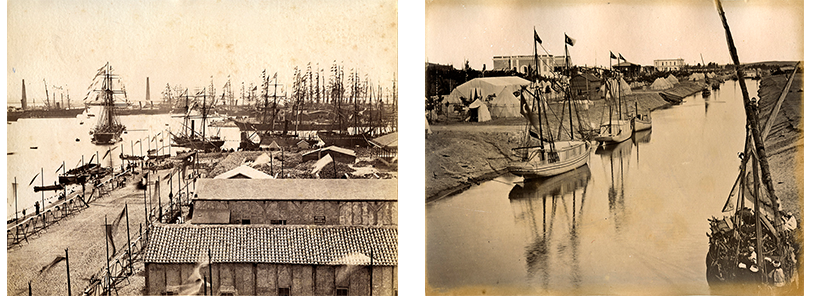

Port Said shortly after the Suez Canal was opened. Workers stand on a jetty made of cement blocks extending out into the sea to protect ships at anchor waiting to enter the canal. Norbert Schiller Collection

After Mohammed Ali died in 1849 and was succeeded with his grandson Abbas I, the next eldest male family member, the idea of the canal was shelved. Abbas I had a completely different plan for Egypt which didn’t include following in his grandfather’s footsteps. Instead of trying to emulate Europe, he turned back the clock, got rid of his foreign advisers, ended all foreign contracts and went as far as to arrest, exile, and even kill influential people who still believed in Mohamed Ali’s progressive policies. The only project that was allowed to continue was the Cairo-Alexandria railway led by Robert Stephenson, a British entrepreneur. Fortunately for De Lesseps, he was transferred to Spain before Abbas I came to power.

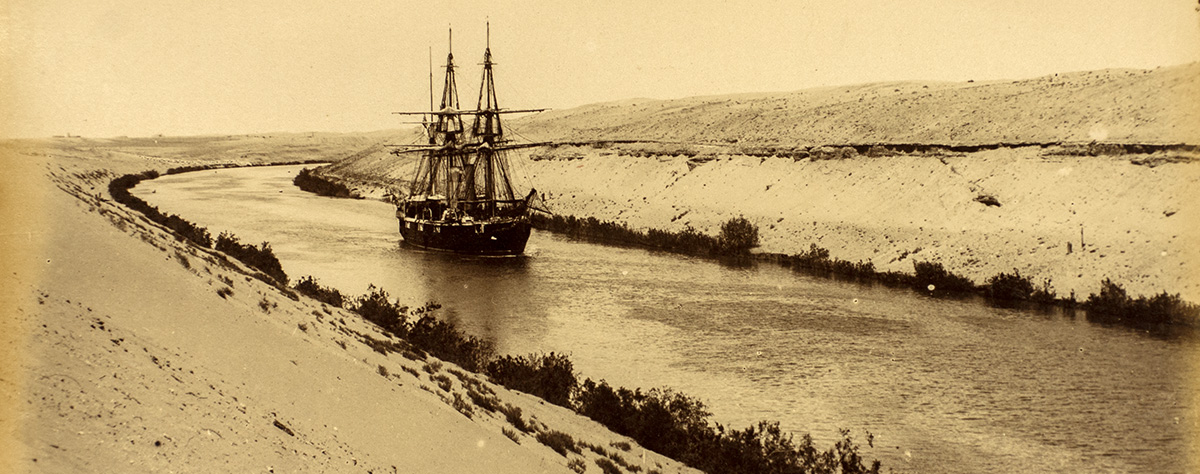

French naval transport ship Vinh-Long rounding the el Ferdan curve in the newly-constructed Suez Canal. A ship nears the Kantara crossing situated halfway between Port Said and Suez. The small boat docked on the landing belongs to photographers Arnoux and Zangaki. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Zangaki

After an eight-year stint in Spain De Lesseps was sent by the French Foreign ministry to Rome in 1849 to negotiate between the warring factions vying for power in the sort-lived Roman Republic. His mission was to reinstate Pope Pius IX who had been forced to flee due to fighting and secure a French presence in Rome to counter Austria’s military presence. Little did De Lesseps know that he was entering a hornets’ nest. After negotiating what he thought was a favorable settlement, the French diplomat returned to Paris, but instead of being rewarded for his efforts, he became the scapegoat for all the failures in Rome. Before he realized what was happening, De Lesseps was relieved of his duties and made to return to civilian life as a disgraced diplomat.

A ship passes a dredger removing sand from the bottom of the Suez Canal.The ship Bataue Olandais rounds el Guirsh curve at the same time a sailboat goes in the other direction. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. (R) Zangaki

In 1954, Abbas I was murdered by two of his slaves under mysterious circumstances, and the mantel of power was handed over to Mohammed Ali’s eldest living son, Said. The first thing that the new sovereign did was reverse the inward and conservative ways of his nephew and continue with his father’s dream of modernizing Egypt. Overnight, the country came out of years of stagnation was back on track to becoming a new regional hub.

When De Lesseps heard of Abbas I’s death, he immediately wrote to Said who invited him to return to Egypt. As soon as he received the offer, the Frenchman set sail for Alexandria, but this time he brought a plan, which he had been working on since leaving the foreign ministry, on how to build a canal through the Suez isthmus. Although De Lesseps returned to Egypt as a normal French citizen, he was given a royal welcome to befit the most distinguished of guests. De Lesseps and the new viceroy had had a long and close relationship. Years before, during the French diplomat’s mission in Egypt, he had mentored the young prince at the request of his father, Mohamed Ali. As a result, Said fell in love with everything French, including the food which he ate in abundance.

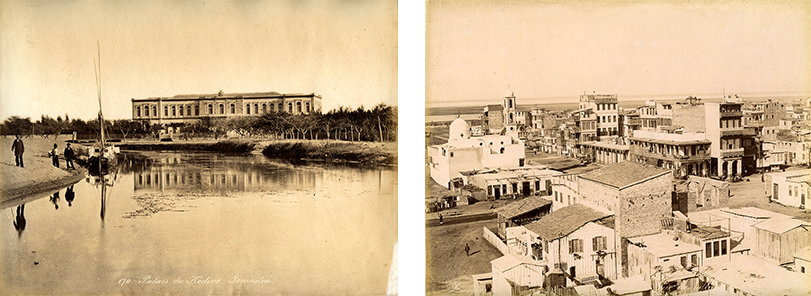

The Khedive’s place in Ismailia. Docked on the shore is the photographers’ sailboat with darkroom. The Red Sea port town at the southern entrance of the Suez Canal. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. (L) Arnoux, (R) Zangaki

Shortly after De Lesseps arrived in Alexandria, he was invited by Said to join him on an overland journey through the Libyan desert back to Cairo. The viceroy wanted to celebrate his coming to power and what better way to do so than to travel with his soldiers on horseback. Every day, after the camp was set up, horsemen performed military maneuvers while bombardiers fired cannons, all to the delight of the young Said. For De Lesseps, this was the perfect time to breach the subject of the canal. Late one afternoon, while everyone had settled into their tents De Lesseps went to see Said to discuss the canal, what it would mean for Egypt, the Ottoman empire, the world at large and most importantly, to Said’s legacy. And last but not least, De Lesseps put himself forward as the best candidate for this project. After a long discussion, Said gave the former diplomat a verbal green light. From that day on November 1854, until the canal was finally inaugurated 15 years later almost to the day, De Lesseps worked tirelessly to implement his dream project.

Ferdinand de Lesseps’ cousin, Empress Eugenie of France. N. Schiller Collection

For the next five years, De Lesseps traveled from one European capital to another trying desperately to raise the 200 million Francs he estimated it would take to build the canal. In the end, the price was well over double that amount. Wherever he went, he met stiff opposition including from the Saint-Simonians who accused him of hijacking their idea. But the most aggressive opposition came from the British who were completely against the plan, fearing that they would lose influence over Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean. Even though French emperor Bonaparte Napoleon III was privately favorable, he never endorsed the project publicly for fear of getting into conflict with the British. However, in spite of all the colossal challenges, including Said’s ambivalence for fear of upsetting the Ottoman Sultan who had not been consulted, De Lesseps had one trump card that played in his favor and that was his younger cousin Empress Eugènie de Montijio, Napoleon’s wife. Due to their close relationship, De Lesseps never hesitated to use Eugenie’s influence when he needed it.

The actual work on the canal commenced in April 1859. To get sufficient manpower, the controversial Corvée system was implemented making it possible to force low skilled farmers to work basically as slaves, for the betterment of the country. Before any real serious excavation could begin, a freshwater canal had to be dug from the Nile to the canal zone to provide drinking water for the hundreds of thousands of workers whose unfortunate fate was to carry out this gargantuan task.

After a few years, very little had been accomplished and it seemed that manpower alone was not enough. It was no secret that the viceroy’s health was failing as his overindulgent lifestyle was taking a toll on his body. In January 1863, at age 41, Said passed away and was succeeded by Mohammed Ali’s next eldest heir, Ismail Pasha. Ismail was a grandson of Mohammed Ali and the son of Ibrahim, who had taken over the running of the state when his father was ailing but died shortly before his father. Ismail, who later was given the title Khedive, had also spent a fair amount of time in Europe. Consequently, his grandiose dream was not the Suez Canal, but transforming Cairo look into a Paris on the Nile. At the same time that money was being spent to finish the Suez Canal, Ismail was financing the capital’s facelift. He did that by increasing the cotton yield and taking out more loans from European banks. In the end, Ismail’s policies bankrupted the country leading to his forced exile and Egypt’s surrender to the European powers, France and Great Britain.

At about the same time that Ismail came to power, the British were trying to stamp out slavery in their colonies, so they put pressure on the Khedive to end to the Corvée. It’s not clear whether the British were really interested in the fellahin’s wellbeing or if they had ulterior motives to disrupt work on the canal. Ismail, on the other hand, also wanted an end to the servitude system because he needed the farmers back in the fields to growing the cotton needed to meet his financial demands. For De Lesseps, the decision came as a blessing because it forced him to switch over to mechanized steam dredgers to finish the job.

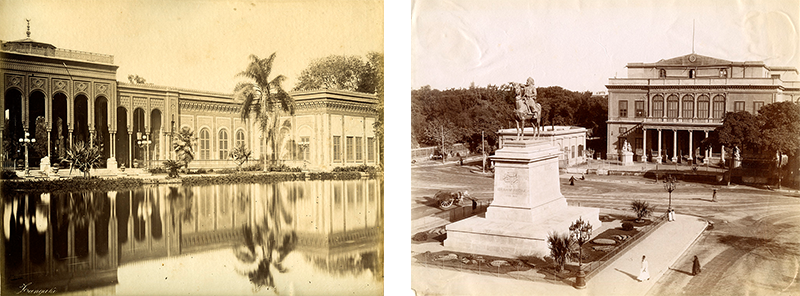

The Gezira Place built on an island in Cairo for Empress Eugenie when she came to open the Suez Canal. The Cairo Opera House standing behind a statue of Ibrahim Pasha in the center of Cairo was built for the opening performance of Verdi’s Aida. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. (L) Zangaki

The completion date was scheduled for October 1869 and the inauguration ceremonies were set for November 17th. All of Europe’s royalty were invited along with organized package tourist groups. It was no surprise that the guest of honor was non-other than Ferdinand De Lesseps’ cousin, Empress Eugenie. Before launch date, a few other projects, related to the canal, still had to be finished. One was the new opera house in the center of Cairo where the Khedive was hoping to stage the opening of Verdi’s opera Aida. However, Verdi missed the opening date and his opera wasn’t shown until a few years later. The second project was a new palace on the Gezira (island) in Cairo, to serve as a residence for Empress Eugenie. Today that palace is managed by the Marriot hotels.

The inauguration of the Suez Canal at Port Said on 17 November, 1869. Tents set up at Ismailia for festivities the following day. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Sebah

On opening day, around 60 ships gathered at the canal entrance in Port Said, led by the empress Eugenie’s imperial yacht, L’Aigle. At the end of the first day, the flotilla made it to Ismailia after crossing half the distance to Suez. In Ismailia, there were celebration that lasted all night and well into the next day. On the third day, the fleet continued onto Suez from where all the VIPs were whisked away by train to Cairo while the others had to figure out their own way back.

Today, the Suez Canal continues to serve its original mission, which is to shorten the distance it takes for goods to travel to and from the Far East. It many ways, it is one of the few lasting success stories of the 19th century that is still as relevant today as it was when it was first conceived.

NOTE–The research for this story came from a number of sources, most notably, Zachary Karabell’s book, Parting the Desert, The Creation of the Suez Canal. Published in 2003.

Dear Norbert

I have read your account with great interest. I own a gold brooch depicting the sphinx by the Australian goldsmith Steiner probably made to commemorate the opening of the canal in 1869. This venture made a trip to England far shorter and was of great benefit to the gold industry in Australia. Is their any record of ships and their cargos from South Australia home of a mint through the canal?l