by Michelle L. Woodward

What is Orientalist photography? The term “Orientalist” is often used to describe photography of the Middle East, particularly those images produced in the nineteenth century. Although the word Orientalist at one time referred to a scholar of the “Orient,” it is now used almost exclusively to refer to a particular system of representation that creates a false distinction between a supposedly tradition-bound “Orient” and a modernizing “West.” Orientalist photography depicts the Middle East as exotic, erotic, and mysterious; constrained by religious beliefs; and as unable or unwilling to progress and change without outside, specifically European, interference. Orientalist photography recycles familiar stereotypes and clichés in order to create a fictional world that matches the preconceived notions of the audience and assures them of their superiority.

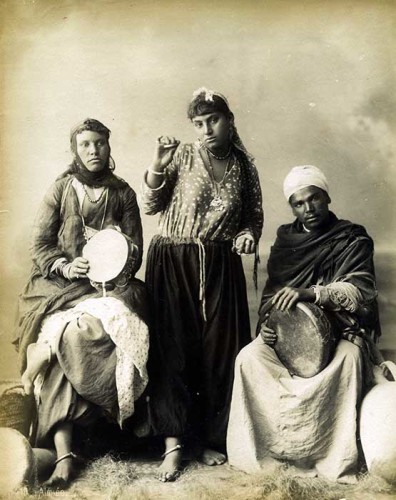

(figure 1) Orientalist cliché of a dancer posing with musicians in Egypt, circa 1880s. Norbert Schiller Collection, unknown photographer.

Edward Said’s influential 1978 book Orientalism generated this new meaning of the word Orientalist. Said’s argument traces how Europe manufactured an imaginary Orient through literary works and the social sciences that was intertwined and complicit with imperial, colonial ambitions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Many scholars expanded upon Said’s insights in order to analyze art, photography, and architecture. Initially the concept of Said’s Orientalism was used in the field of photography to uncover, and critique, the fictitious stereotypes and demeaning tropes present in much European photography of the Middle East. Research on photography of the Middle East has deepened over the past few decades to include more histories of indigenous photographers and a wider range of categories of photography, while still demonstrating how Orientalism is a useful critical concept. Some scholars have also looked within the Middle East for counter-responses, resistances, and engagements with the European Orientalist vision. The discussion continues to expand as scholars investigate photographic practices in specific historical, social, and territorial contexts with various degrees of engagement with the concept of Orientalism.

The visual conventions of late nineteenth-century photographs of the Middle East varied widely depending on audience and purpose. A brief analysis of street photographs created by the Sébah family commercial studio in Istanbul will be compared in this essay to the work of the prolific Bonfils family studio located in Beirut. The focus here is on how these two long-standing studios chose to photograph people in public places such as markets, streets, mosques, and baths in the period 1870-1900. Looking closely at this portion of the two studios’ works, it is possible to discern different approaches. It appears that the Bonfils photographs were generally unable to transcend popular European stereotypes of the “Orient” while the Sébah family developed a mode of representation that presented a detailed view of local Ottoman society without resorting to the clichés of Orientalism. In this way, it is the purpose of this essay to show how Orientalism is a useful lens for analyzing the photography of this period, but that not all products of commercial photography studios can be labeled Orientalist.

It is important to note that Orientalist clichés and tropes were used by both Western and local photographers alike. Regardless of the photographer’s national origin or identity, the photography they produced was influenced by the tastes of their intended audience or clientele, among other factors. Whether they were local or foreign, photographers were susceptible to the pressures of the market and most produced stock Orientalist fare for tourists, as well as other types of work.

(figure 2) Landscape showing Mount Horeb with St. Catherine’s Monastery on Egypt’s Sinai peninsula, circa 1860. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Francis Frith

Nineteenth-century photographic activity in the Middle East spanned a wide range of different genres, as it did in other parts of the world. There are the well-known fictional Orientalist clichés, often created in the studio, such as erotic harem scenes and models posed as traditional musicians, craftsmen, or merchants (figure 1) and landscape scenes meant to evoke Biblical stories or reinforce stereotypes of an undeveloped society. In addition there are photographs of historical monuments, artifacts, and archeological sites (figure 2); professional studio portraits of individuals and families (figure 3); early documentary and street photography (figure 4); and propaganda images such as those depicting modernization commissioned by the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Other genres such as commercial, advertising, medical, industrial, amateur, scientific, and news photography were also part of the late nineteenth-century visual world but are not well represented in the archives and thus less well-studied.

(Figure 3) A woman from Alexandria Circa 1890s. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. G. Lassave

Generally speaking, late nineteenth-century photography worldwide may at first appear to have a uniformity of style, an easily recognized look. There are certainly characteristics of photographs made in this period that are broadly consistent, such as the sharp focus and minute detail provided by the use of large glass plate negatives. There was also a widespread interest in cataloging people according to ethnic group or occupation as well as commonalties in the use of studio backdrops, props, and poses. However, a deeper study of photographic practices shows that the meaning and use of common conventions varied across national boundaries as well as within them.

Photography and European desires

The desire by Europe to document the Middle East in photographs existed from the first unveiling of the photographic process. In his August 1839 public announcement in Paris of Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s invention of the daguerreotype, French scientist and politician François Arago described the great future potential of this new process with the following example:

“How archeology is going to benefit from this new process! It would require twenty years and legions of draftsmen to copy the millions and millions of hieroglyphics covering just the outside of the great monuments of Thebes, Memphis, Karnak, etc. A single man can accomplish this same enormous task with the daguerreotype.”

The nineteenth century’s passion for cataloging, collecting, and explaining the world in scientific, empirical terms manifested in the formation of new disciplines such as anthropology and sociology, new theories like Darwin’s evolution, as well as in the ways society used the new technology of photography. The photograph’s ability to record more life-like detail than any other process led to its use as a tool for accumulating visual surveys of urban space, historical monuments, colonial possessions, and people categorized as ethnic or occupational “types.” The Middle East was soon subject to these visual surveys of landscape, architecture, and people. An early example is the work of Egyptian engineer Muhammad Sadiq Bey (1832-1902) who was the first to photograph Mecca and Medina in 1861 during the course of a cartographic expedition.

(figure 4) A market scene in Biskra, Algeria. Circa 1880s. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Alexandre Leroux.

By the time Daguerre’s photographic process was announced in Paris as a new invention, European popular interest in the Middle East had already been firmly established. Middle Eastern motifs had been appropriated for use in clothing fashions, literature, music, furniture, drawings and paintings since the sixteenth century. As soon as photographers developed ways to photograph outside their own backyards they immediately headed to Egypt, Palestine, and Istanbul. The earliest photographers to travel from Europe to the Middle East did not photograph for commercial purposes, but were primarily wealthy tourists or explorers of archeological ruins (often for government sponsors) such as Maxime Du Camp, traveling with Gustave Flaubert, and Auguste Salzmann. By the late 1850s the wet collodion process of making glass negatives allowed for the creation of multiple, more affordable prints for broader distribution. From the 1860s, photographers like Francis Frith and Félix Bonfils quickly found commercial success with a European public fascinated by the “East” as well as with tourists travelling in the region seeking mementos to take home.

Early in photographic history, indigenous photographers opened commercial photography studios. These included Pascal Sébah (later Sébah and Joaillier) in Istanbul and Cairo, Garabed Krikorian in Jerusalem, Abdullah Fréres and Vasilaki Kargopoulo in Istanbul, and many others. At the same time, numerous European photographers established studios in the major cities of the region. Some of the more famous European studio photographers include Maison Bonfils in Beirut, Antonio Beato in Luxor, Zangaki brothers in Port Said, Guillaume Berggren in Istanbul, Antoin Sevruguin in Tehran, and Lehnert and Landrock in Tunis and Cairo.

(figure 5) A view of Istanbul, the Golden Horn and Topkapı palace most likely taken from the Galata Tower, circa 1890. Norbert Schiller Collection, Unknown photographer.

Relations between the Ottoman Empire and Europe

In the late nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire still governed a large area of the Middle East. Although people in the region interacted with many European social forces, not all were subject to Western colonial rule. When photography was officially revealed, in 1839, Europe had economic and political interests in the Middle East. Just the year before photography’s historic debut the Ottoman Empire had signed the Anglo-Ottoman Convention, the first of several treaties that opened up the Ottoman provinces to European merchants, giving them unprecedented access to markets. Since the eighteenth century the Ottoman sultans had been implementing reforms, based on European models, in military, educational, technological, and scientific fields. Inspired by Eugène Hausmann’s rebuilding of Paris in the late nineteenth century, architectural and urban planning efforts had begun to transform Istanbul.

Socially, Istanbul had been an ethnically diverse city since the Byzantine era when foreign colonies settled for purposes of trade. After various treaties with Europe gave preferential treatment to European merchants in the mid-nineteenth century, the population of foreign residents grew and, by 1885, they made up almost fifteen percent of Istanbul. The districts of the city which had the highest concentration of foreigners were Péra and Galata (figure 5). It was in Péra, on the Grande Rue de Péra, where most photographers had their studios. This main street featured up-to-date European-style shops, restaurants, cafes, theaters, department stores, hotels, and apartment buildings. Foreign tourists as well as the local elite, including members of the Ottoman court, frequented the district.

(figure 6) Turkish school girls dressed in European clothes, circa 1890s. Abdul Hamid II Collection. Phot. Abdullah Freres

In this time of rapid modernization, photography was seen as another advanced technological tool that could benefit the Ottoman Empire. The sultans encouraged the use of photography from its beginnings, but it was Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876 – 1909) who is considered its greatest supporter. Abdul Hamid seems to have understood the persuasive and propaganda value of photography and, in the early 1890s, he commissioned the production of fifty-one albums depicting the modernization of the Ottoman Empire through photographs of architecture, educational institutions, students in European dress (including many girls), military arsenals, hospitals, factories, and docks, among other subjects (figure 6). In commissioning the photographs for the albums, the sultan remarked that “Most of the photographs taken [by European photographers] for sale in Europe vilify and mock Our Well-Protected Domains. It is imperative that the photographs to be taken in this instance do not insult Islamic peoples by showing them in a vulgar and demeaning light.” After being exhibited at the World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, sets of the albums were donated to the United States Library of Congress and the British Museum as evidence of Ottoman progress. It is not clear, however, if these albums were actually viewed by anyone in the receiving countries, and thus their diplomatic effectiveness has been called into question.

(figure 7) Syrian Moslem women photographed inside a studio in Beirut, Lebanon, circa 1880s. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Bonfils

Commercial photography studios

Commercial photography studios produced most of the images labeled now as Orientalist. They were often run by permanent residents in the Ottoman Empire who established long-lasting local studios, unlike those photographers who traveled in the Middle East for a short period and then returned to Europe with their negatives. The Frenchman Félix Bonfils, for example, established a family-run studio after moving to Beirut in 1867. His subjects included all the usual themes from Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Greece: monuments, landscapes (often titled with Biblical references), and people classified according to type (figure 7). Many studios photographed people as recognizable types posed and costumed as if engaged in traditional and timeless activities, such as brewing coffee, selling produce, praying, or playing musical instruments. Certain Bonfils studio shots of types have been shown to be falsely labeled, with the same model posing as a rabbi in one photo and a cotton carder in another. Scholars have found that the use of models was a common practice among studios.

What makes a large portion of the Bonfils family’s work Orientalist was their explicit effort to capture what they imagined was a timeless, unchanging Middle East on the verge of disruption by an external, imported modernity. By selectively and deliberately choosing only particular elements from the surrounding environment to include in the picture, such as rural landscapes, traditional clothing, and props that suggest pre-modern occupations, they strove to meet their, and other Europeans’, expectations and interests. Adrien Bonfils, wrote that “Before that happens, before Progress has completed its destructive work, before this present – which is still the past – has disappeared forever, we have tried, so to speak, to fix and immobilize it in a series of photographic views.” The Bonfils family was not interested in illustrating present-day realities, but preferred to recreate for the camera what they saw as the region’s “pristine character and special cachet.” This desire can be seen in their posed photographs of lone water-sellers, carpet merchants, tinsmiths, and other occupational and ethnic types, as well as in their deliberate focus on the traditional, rural, and Biblical, to the exclusion of all indications of modernity.

Studios owned by indigenous photographers also produced Orientalist work. Pascal Sébah, whose parents were Syrian Catholic and Armenian, established a studio in Istanbul in 1857, later expanding his work to Cairo. His studio produced views of monuments, city streets, landscapes, and family portraits, as well as the usual Orientalist material such as staged scenes of ethnic types and women posing seductively. Pascal Sébah’s son, Jean, who took over the Istanbul studio after his father’s death, was commissioned with his French partner Polycarpe Joaillier to provide photographs of neatly arranged rows of school children across the empire to add to Abdul Hamid’s albums, which depicted Ottoman modernization. They also documented the antiquities in the archeology museum in Istanbul.

(figure 8) Interior of the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, circa 1890s. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Sabah & Joaillier

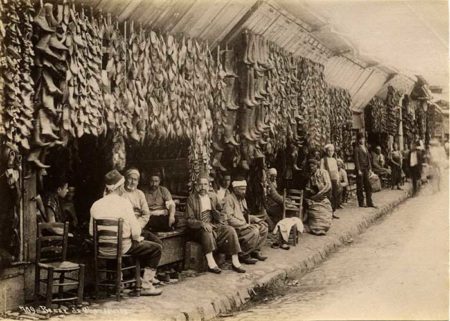

(figure 9) Shoe makers market in Istanbul, circa 1890s. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. Sabah & Joaillier

Most uniquely, the Sébah studio produced documentary-style photos taken in city streets and inside markets and mosques with what appear to be actual residents or pedestrians, often sitting or standing as if posed for a portrait. These are not models and they are not pretending to be working or wielding excessive props to signify their identity as types. In this period the arrangement and posing of people for a photograph was deliberately decided by the photographer due to slow shutter speeds and large, heavy camera equipment that required a tripod. But beyond the necessary basic arranging and directions to keep still, many photographs of public places by the Sébah studio seem to depict people as modern-day individuals, gazing confidently at the camera as they pose in their usual environments, rather than as Orientalist types.

The Sébah studio was certainly not the only one to create documentary-style images reflecting daily life in the Middle East. However, their well-composed and technically accomplished images provide a useful example of a different type of photography that co-existed with the Orientalist genre. The Sébah studio took many photographs of Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, a place well-known to tourists. In this example, Sébah arranged merchants to appear lined up in front of their shops (figure 8). The composition of this and other similar photographs locates the subjects in their social context (figure 9). By intentionally angling the camera so that it captures the length of the street, Sébah shows how the market is structured with shops that sell fabric or clothing clustered in the same area. He also dismisses stereotypes about his subjects by showing that not all fabric merchants dress alike. Additionally, the photo reveals the variety of men and boys present in this social space. These visual revelations may seem trivial, but they are quite different from the impressions given by a more typical nineteenth-century image of types that carry Orientalist implications of the Middle East as a place outside of time (figure 10). In those staged studio photos of occupational types, individual or social details are consciously omitted. Backgrounds are painted and assembled like stage sets and thus reveal nothing about the individuals or about the city fabric. In this style of photograph, the focus is on the body and the symbolic props or postures displayed, which reinforce stereotypes known to Europeans. In contrast, Sébah’s portrait style emphasizes a group of individuals and their connections to a larger society, exposing a complex and subtle interaction and thus eluding easy stereotyping.

(figure 10) Staged studio scene of a bread seller in Egypt, circa 1865. Norbert Schiler Collection, Phot. F. Meissner,

Between Orientalism and Modernity

A portion of the Sébah family’s photographic output made use of conventional Orientalist clichés prevalent at the time in depictions of the Middle East, prompting some writers to label their work as Orientalist. However, upon close examination, some of their work also reveals a vision of the Ottoman Empire that is different from the typical Orientalist genre. In particular, their portraits of everyday people in public settings, which emphasize order and modernity within indigenous historical structures and at the same time depict places and peoples that tourists were curious about — such as markets, merchants, bath houses, and mosques — indicate a perspective that does not fit comfortably into the Orientalist mode.

As Zeynep Çelik noted in the context of Ottoman representations in the late nineteenth-century world fairs, while “many Muslim nations accepted European supremacy and attempted to remodel their institutions according to Western precedents, they were also searching for cultural identity under the strong impact of European paradigms.” She goes on to suggest that “European paradigms were not simplistically appropriated; they were often filtered through a corrective process, which reshaped them according to self-visions and aspirations.” Similarly, the Sébah family’s photographic studio may have creatively adapted some European conventions, such as photographs of occupational types to suit their “self-visions” as a society with its own illustrious history, which was modernizing from within and not simply adopting European models.

Timothy Mitchell’s book Colonising Egypt explains how the colonizing process undertaken by Britain in Egypt was designed to impose order on what was seen as a system without structure. Mitchell reproduces a Bonfils photograph of the al-Azhar mosque in Cairo as an example of European descriptions of what they saw as the disorder prevailing in this teaching-mosque. Bonfils’ outdoor scenes (and those of many other photographers) often give an impression of disorder and decay, which had the potential to validate European intervention in the Middle East. The Sébah style described above counters the prevailing image of disorder with an image of a non-western, locally-produced order and structure. In many of their street portraits, order and structure are emphasized through people’s dress and attentive and composed demeanor, but also in the architecture of buildings and the organization of shops.

While much nineteenth-century photography of the Middle East portrayed the region in an Orientalist manner, not all photography of the Middle East is Orientalist. A closer examination of a portion of the Sébah studio’s work in contrast with another prominent studio, that of Bonfils, provides an example of a different mode of depicting the Ottoman Empire. In particular Sébah’s street portraits, which emphasize order and authenticity in everyday life, indicate a perspective that does not conform to Orientalist clichés and suggest that there are myriad and divergent factors that influenced local photographic practices, beyond that of European imperial power and Orientalist preconceptions.

——

1For examples, see Malek Alloula, The Colonial Harem, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 1986, Sarah Graham-Brown, Images of Women: The Portrayal of Women in Photography of the Middle East, 1860 – 1950, New York: Columbia University Press 1988, and Nissan N. Perez, Focus East: Early Photography in the Near East (1839 – 1885), New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in association with The Domino Press, Jerusalem, and The Israel Museum, Jerusalem 1988.

2For examples in the Ottoman world of photography, see the work of Engin Özendes and Bahattin Öztuncay on the history of Ottoman photographers. Also see Nancy Micklewright, Edhem Eldem, Ahmet Ersoy, and Zeynep Çelik, among others, for expanding how photography can be used in writing history. Stephen Sheehi’s recently published book The Arab Imago: A Social History of Portrait Photography, 1860 – 1910 (2016: Princeton University Press) is an important work on the history of indigenous photography in the region. For scholarship that attempts to complicate the relationship between photography and Orientalism while still embracing Orientalism as a crucial framework, see Photography’s Orientalism: New Essays on Colonial Representation, edited by Ali Behdad and Luke Gartlan, 2013: Getty Research Institute.

3See the work of Zeynep Çelik, as one example. Ahmet Ersoy describes how the Ottomans used the European Orientalist tradition as “a contested space for fleshing out local agendas and for enunciating projected differences as well as internal alterities.” (“Osman Hamdi Bey and the Historiophile Mood: Orientalist Vision and the Romantic Sense of the Past in Late Ottoman Culture,” in The Poetics and Politics of Place: Ottoman Istanbul and British Orientalism, 2011, p. 145.) Ottoman Orientalism, developed within the Ottoman empire, has been described by Ussama Makdisi and Selim Deringil.

4For an example of new work on Ottoman photography that attempts to move beyond the framework of Orientalism, while still taking it into consideration, see Camera Ottomana: Photography and Modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840 – 1914, edited by Zeynep Çelik and Edhem Eldem, 2015: Koç University Publications.

5For examples of studio photography around the world see: Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, Paris: Revue Noire 1999. Wendy Watriss and Lois Parkinson Zamora, Image and Memory: Photography from Latin America, 1866 – 1994, Austin: University of Texas Press in association with FotoFest, Inc. 1998. For a European example of categorizing members of society by occupation see the work of the German photographer August Sander.

6Gisèle Freund, Photography and Society, Boston: David R. Godine 1980.

7The census of 1885 quoted in Zeynep Çelik, The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century, Berkeley: University of California Press 1986.

8European experts were brought to Istanbul to assist with modernization efforts. Two of these experts, Enest de Caranza and James Robertson, were also photographers who pursued their avocation while in the Ottoman Empire. Bahattin Öztuncay, ‘Ernest de Caranza: Member of the Société Française de Photographie’, History of Photography 15:2 (Summer 1991), 139-43. Bahattin Öztuncay, James Robertson, Pioneer of Photography in the Ottoman Empire, Istanbul: Eren 1992.

9Quoted in Selim Deringil, The Well-Protected Domains: Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire 1876 – 1909, London: I.B. Tauris 1998, 156.

10See Carney E.S. Gavin, Sinasi Tekin and Gönül Alpay Tekin, ‘Imperial Self-Portrait. The Ottoman Empire as Revealed in Sultan Abdul Hamid’s Photographic Albums’, Journal of Turkish Studies 12 (1988).

11Edhem Eldem, “Powerful Images: The Dissemination and Impact of Photography in the Ottoman Empire, 1870 – 1914,” Camera Ottomana: Photography and Modernity in the Ottoman Empire 1840 – 1914, Istanbul: Koç University Publications 2015, 114.

12Perez, Focus East: Early Photography in the Near East (1839 – 1885), 141.

13Carney E.S. Gavin, The Image of the East: Nineteenth-Century Near Eastern Photographs by Bonfils, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press 1982, 1.

14Ibid.

15For an expanded discussion of the work of the Sébah studio, and that of the Bonfils studio, see Michelle L. Woodward, “Between orientalist clichés and images of modernization:

Photographic practice in the late Ottoman era,” in History of Photography, 27:4 (Winter 2003).

16For one example see Özendes, From Sébah & Joaillier to Foto Sébah: Orientalism in Photography.

17Çelik, Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at 19th Century World’s Fairs, Berkeley: University of California Press 1992, 10-11.

Fantastic blog! Nothing comparable to it.

Thanks for your outstanding curatorship.

Will whoever controls gene editing control historical memory? | DJG Blogger

[…] populations – becomes clear. Feminists spoke of the male gaze. Postcolonial theorists pointed to orientalism. And environmentalists have shown how human progress is destroying the physical […]

Theories and Analysis – UH x TAFA 2020-21

[…] http://www.photorientalist.org/about/orientalist-photography/ (follow the link and read the blog post – its’ good!) […]

Another article - Orientalism & photography - Melroy D'silva

[…] Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Photography […]

Will whoever controls gene editing control historical memory? - FactsandHistory

[…] – becomes clear. Feminists spoke of the male gaze. Postcolonial theorists pointed to orientalism. And environmentalists have shown how human progress is destroying the physical […]

Artists Decolonizing Colonial Depictions of Women from the Middle East and North Africa – Land of Galleries

[…] the 1800s, the Daguerre photographic process became popular, and wealthy European photographers were funded by colonial governments to travel and document the […]

I came across this website randomly while researching Middle East in the 1960s and now. Two hours later, after delving into so many perspectives new to me, I am writing this thank you note. Understanding, especially through photographs, is so crucial, so important. But, photographs accompanied by insights (warnings? as in the Orientalism and Zionist sections?) are precious. Again, thank you.