By Norbert Schiller

Photographs and illustrations from my personal collection

The main causes for the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War, which included the bombardment of Alexandria and the battles of Kfar al Dawwar and Tel El Kibir, were foreign modeling in Egypt’s affairs. From the time that Mohammed Ali took over in 1805 until his dynasty was overthrown 148 years later, England, France and the Ottoman Empire competed for control in Egypt. While the three superpowers strategized amongst each other for supremacy, Mohammed Ali and his heirs had to walk a narrow line to appease the outside powers, while working in the best interest of the Egyptian people, at least in appearance.

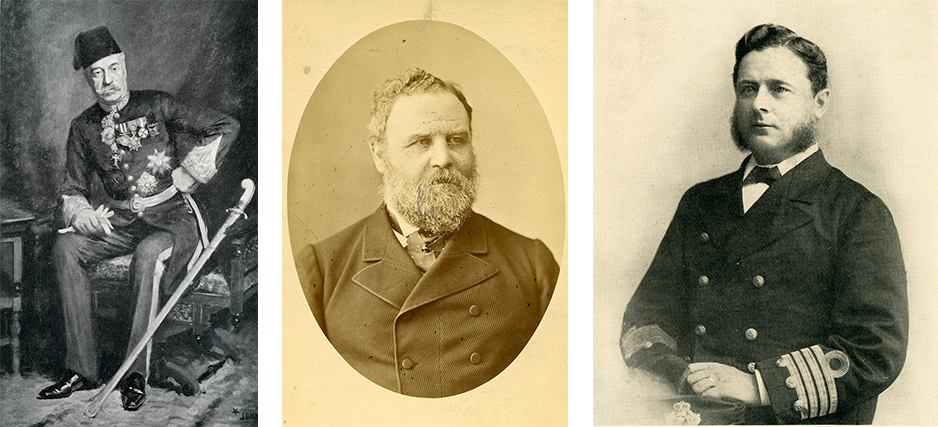

The three Egyptian leaders whose policies led to the Anglo-Egyptian War. (L to R) Said Pasha gave the Suez Canal concession exclusively to the French entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps. Ismail Pasha financially ruined Egypt by building a new Cairo, while launching a failed invasion of Ethiopia. Khedive Tewfik watched hopelessly as his Minister of War, Ahmed Urabi, hijacked the military. Phot.(L) McLean, Melhuish & Haes (C) Claudius Couton (R) H. Dilie & E. Bechard

Ferdinand de Lesseps. Phot. unknown

The main point of contention, which was at the root of the conflict, was the building of the Suez Canal. From its conception, when French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps won the concession to build the canal until it was completed 15 years later, the project was wrought with controversy. The very fact that De Lesseps was granted the concession alone caused shockwaves among Europe’s power elite, most notably the Saint-Simonians. This influential group of scientists, engineers and architects from all over Europe believed in promoting the use science and technology for the benefit of the working class. Since the beginning of Mohammed Ali’s reign, the Saint-Simonians were devising plans to use Egypt as a transit point for goods going to and from the Far East, to avoid the long journey around Africa. De Lesseps, who happened to be one of the Saint Simonians, was working with the group to find a solution, but when they could not agree on a plan, the Frenchman decided to act alone. He succeeded in selling his idea of digging through the Suez isthmus to Mohammed Ali’s Son, Said, shortly after the latter came to power. What infuriated the Saint Simonians was that De Lesseps, who had been Said’s tutor when the young prince was studying in France, used his personal connections to win the concession for himself. De Lesseps’ scheme, however, backfired when he attempted to raise funds for the project in Europe where he was met with stiff opposition. In the end, the canal project went way over budget, and, when Said unexpectedly died, his son and successor Ismail Pasha, had to step in and buy up the unsold Suez Canal shares so the project could continue on schedule.

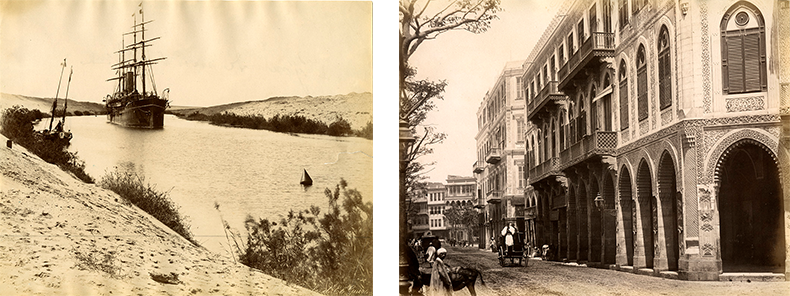

The Suez Canal, which cut the distance for moving goods and people to and from the Far East, was both a blessing and a curse. The canal project, combined with Ismail Pasha’s determination to build Paris on the banks of the Nile, led Egypt to a financial ruin. Phot.(L) Zangaki (R) unknown

The Egyptian army performing military exercises. Phot. M. Rassing

Ismail Pasha’s second blunder was his military exploits into Ethiopia. When he heard that European powers were expanding their influence to Africa, he decided to do the same. After first capturing Sudan’s Darfur region and making himself Khedive of Egypt and the Sudan, Ismail Pasha decided to conquer the Nile, namely the Blue Nile that originated in the Ethiopian highlands. After two failed military campaigns into Eritrea and Ethiopia in 1874 and 1876, which cost the Egyptians thousands of lives as well as huge financial losses, there was serious discontent within the Egyptian army. Ahmed Urabi, a young Egyptian officer, who fought in the Ethiopia campaigns, capitalized on these failures and quickly galvanized a following as he rose through the ranks. Urabi was eventually appointed Minister of War by a very reluctant Khedive Tewfik who had recently taken over the throne from his father Ismail Pasha.

Khedive Tewfik was not meant to be a leader. In fact, he became ruler by default when the British and the French pressured the Ottomans to exile his father for mishandling Egypt. In the aftermath of the financial meltdown and the disastrous military campaigns in Ethiopia, the French and British navies sailed to Egypt in an attempt to stabilize the country and help the young Khedive consolidate power. Unfortunately, the opposite happened when Urabi, who now was the most powerful man in Egypt, saw the naval taskforce as a threat to Egypt’s sovereignty.

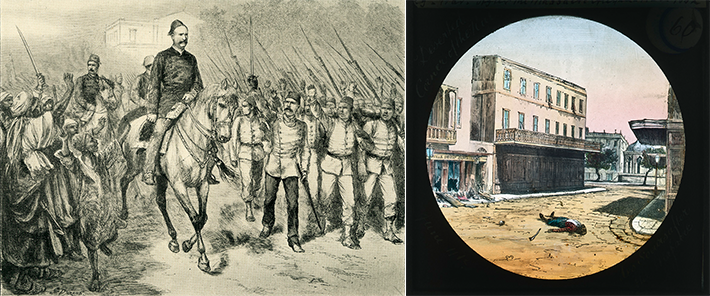

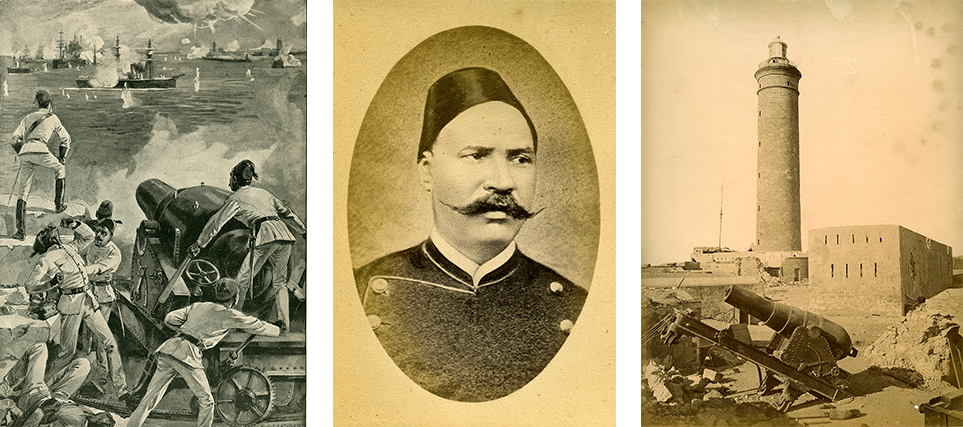

Ahmed Urabi, the most powerful man in Egypt, galvanized the military behind him. After a day of rioting and looting in the European quarter, hundreds of Egyptians and foreigners lay dead in the streets. Illustration (L) Graphic (R) unknown

The last straw was a quarrel that took place on 11 June 1882, a few weeks after the British and French armadas arrived off the coast of Alexandria. A Maltese man got into a confrontation with a local over the fair he had charged him for a donkey ride. This incident quickly escalated leading to street battles in the Maltese (European) quarter of Alexandria between the two sides. When the Egyptian authorities were finally able to stop the violence, hundreds of foreigners and Egyptian had been killed and numerous businesses had been ransacked and looted.

A painting of Kusel Bey in full regalia. Admiral Sir Beauchamp Seymour and Captain Molyneux of the flagship HMS Invincible. Painting (L) Cecil Starr Johns, Phot.(C) J. Maclardy (R) unknown

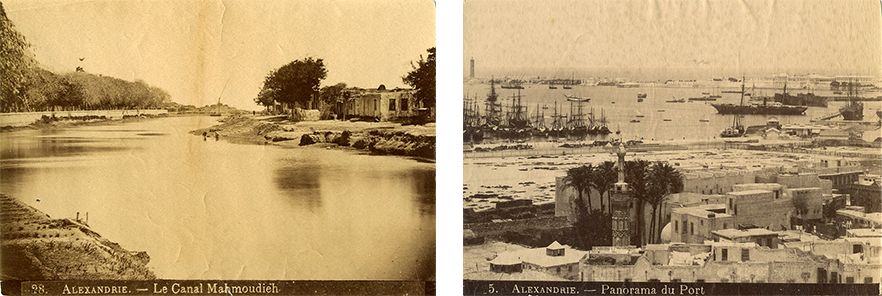

British official Kusel Bey, who held the prestigious post of Controller General of the Egyptian Customs, was entertaining guests not too far from the action. He had invited Captain Molyneux, the commander of the British flagship Invincible to the weekly concert performed by the Egyptian military band on the banks of the Mahmoudieh Canal. Normally the crème de la crème of Alexandrian society would have been in attendance. However, when the two officials arrived in a horse drawn carriage, the park was completely deserted. When he heard the news about the fighting, Molyneux wanted to return immediately to his ship. However, as he and Kusel Bey made their way to the port, the situation deteriorated and the two were forced to take refuge in the British consulate. In his memoir, Kusel Bey describes their harrowing journey.

The Mahmoudieh Canal and the port of Alexandria. Phot. Luigi Fiorillo

“All down the Avenue Rosetta we saw the doors of the houses closed and barricaded, while from the balconies, filled with men and women, many voices cried out to us to stop and not go into town, as the Arabs were massacring all the Europeans, but this only made Captain Molyneux the more anxious to reach his ship; so we did not slacken our pace, and before we knew it we were in the Grand Square, and in the midst of the fighting. My coachman had just time to pull up, and Captain Molyneux, who had stood up and was looking ahead called out that they were murdering that English officer, and that we had better try to reach the Consulate. Bessie, my mare, helped us admirably, for she reared and plunged, keeping the crowd back as the carriage was turned into a side street; we nearly capsized, but with luck, broke through the people, and so round to the British Consulate…We found the consulate in a state of indescribable confusion, women and children crowded everywhere, weeping and terrified.”

The British consul had gone outside to try calm the rioters, but he was attacked and badly injured. The vice consul, whose job it was to take over, collapsed from fatigue. With nobody left to take charge of the consulate, Captain Molyneux, who had just arrived with Kusel Bey, stepped in and took command.

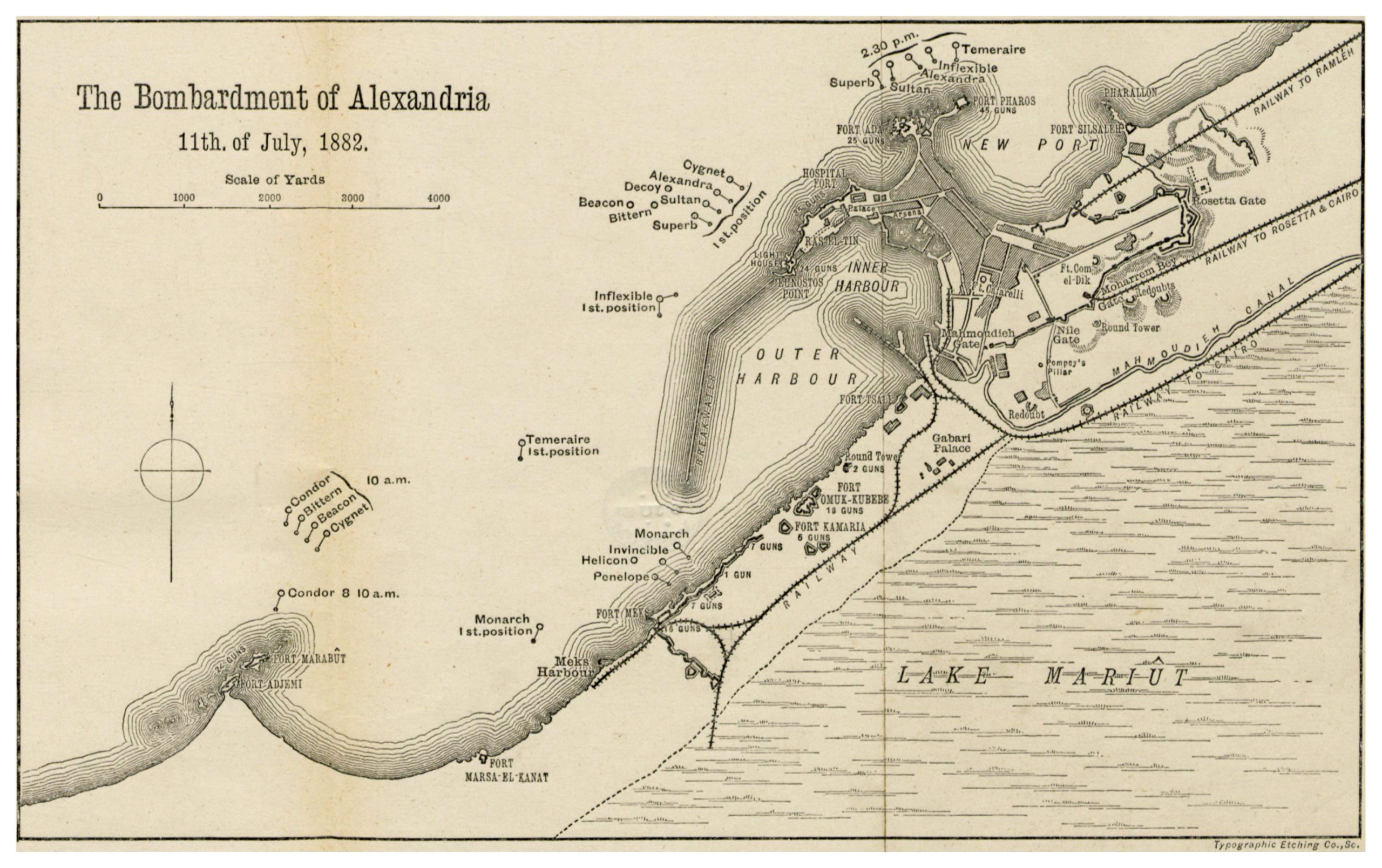

The map showing Alexandria and the positions of British warships during the bombardment

During the one-month period between the violence in the European quarter and the British bombardment, Alexandria became increasingly tense as foreigners began to flee the city by sea. Kheldive Tewfik, was powerless and could only watch from the sidelines as Urabi, the man he had appointed to be Minister of War, began to build up the defenses around Alexandria. The British tried to coax Tewfik Pasha to abandon the palace and take refuge on one of the ships, but he refused saying “I am still Khedive, and I will remain with my people in their hour of danger.” After British Admiral Beauchamp Seymour issued numerous warnings to Urabi to cease building up fortifications, the British planned their attack. Kursel Bey, who by then had relocated to the transport ship S.S. Tanjore, watched the ensuing battle with binoculars from the safety of the anchorage.

The bombardment commenced at 7:00 am and lasted for five hours. The Egyptians fought back striking the British ironclads including the HSM Alexandra which is seen after being hit in the bow. Illustrations (L) unknown (R) Illustrated London News

“The Bombardment of Alexandria commenced on Tuesday, July, 11, 1882 at seven o’clock in the morning…To a civilian who had never seen warfare the spectacle was magnificent. We heard a single gun from the (HMS) Alexandra, which was the signal for the attack to commence, and then one by one every ship joined in until the whole fleet was engaged. It was rather terrible and awe-inspiring, and in spite of myself I trembled with excitement. It was not long before we could see a mass of white smoke which surrounded the ships. We could hear, though we could see little, and the roar of the broadside, the deep booming of the turret guns, and the quick tap-tapping of the Nordenfelt, caused most of our hearts…to beat a trifle faster…In spite of the tremendous and deadly fire from the British ships the Egyptian gunners stuck manfully to their posts, maintaining a heavy fire, their shots striking the ships continually.”

Egyptian soldiers under Ahmed Urabi’s command defending Alexandria. The lighthouse fort is one of many fortifications that were destroyed after five hours of bombardment. Illustration (L) Andre Bleigh, Phot. (L) London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company (R) N. Comianos

After nearly five hours of continuous bombardment a ceasefire was declared. Nevertheless, this didn’t mean the conflict was over. The British continued to engage when they saw attempts by the Egyptians to repair the forts or re-man guns that hadn’t been destroyed. By nightfall, most of the guns had fallen silent, but, an eerie red glow began to rise above the city. Although parts of Alexandria had suffered damage from the shelling, the fires, for the most part resulted from the invasion of the European quarter’s homes and businesses by mobs and looters. After the first day of fighting, the British had suffered 5 death and 27 injuries, and, even though many of the ironclad ships had been hit, none were seriously damaged. On the other hand, the Egyptian casualties were in the hundreds and most of the forts and canons had been rendered useless.

After five hours of British bombing all the forts with their canons were destroyed. Phot. (L) Zangaki (R) H. Arnoux

The artillery batteries at Ada fort in total ruin. Phot. Luigi Fiorillo

The following day, the winds picked up and the sea was rough. Therefore, Admiral Seymore decided to stop the assault for fear that under such conditions the bombing might cause additional collateral damage. Still, Alexandria continued to burn well into the night. “For as night fell we once again had the anxiety of watching a city gradually being destroyed by fire.” Kusel wrote. “From time to time we watched the ever-reddening sky we would see fresh outbreaks of fire in different quarters of town, and it was evident that mob law ruled in Alexandria.”

The first foreign troops that landed in Alexandria were 150 American sailors and marines ordered to secure the American Consulate. Shortly after their arrival on 13 July, the Americans began to restore order, and put out some of the fires. The US landing put pressure on Admiral Seymore who sent a detachment of marines and Bluejackets (sailors) the following day to secure the Palace of Justice and Ras el Tin Palace. That same day, Khedive Tewfik made an appearance at Ramleh Palace, where he had been taking refuge. He had survived an assassination attempt by his own soldiers whom he had to bribe to protect him instead.

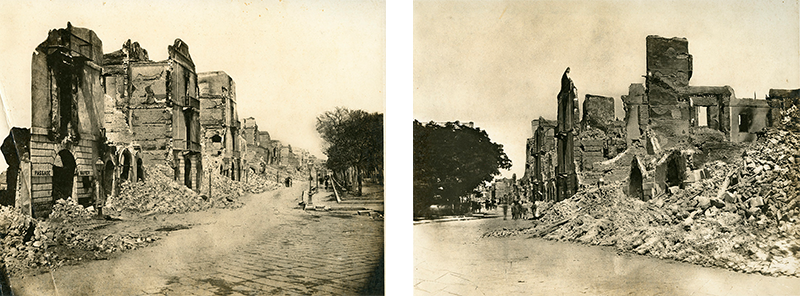

“The Grand Square (Place de Counsel), which before the bombardment had been a source of pride, was now almost completely destroyed.” Phot. Luigi Fiorillo

Kusel Bey, who had come ashore with a detachment of Bluejackets, described what he saw. “Some streets were a mass of smouldering ruins, great heaps of rubbish and tottering walls…Then there were dead bodies, telegraph wires and miscellaneous articles broken and thrown away. In some places the houses were still on fire or smouldering…To one who had been really attached to Alexandria it was infinitely painful to see the ruins. The Grand Square (Place de Counsel), which before the bombardment had been a source of pride, was now almost completely destroyed. The French and Italian Consulates had a few walls left standing, so had the British, but absolutely gutted.”

The French (L) and British consulates were totally ruined after the looting and burning that took place in the wake of the bombardment. Phot. Luigi Fiorillo

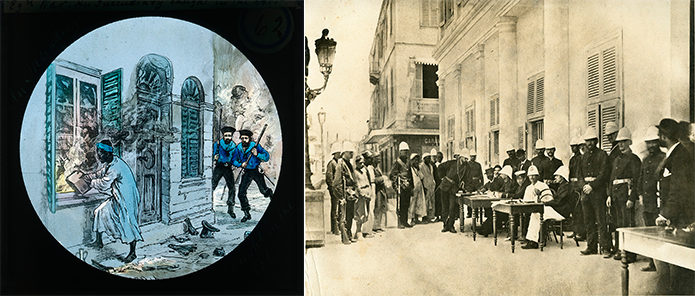

After the Egyptian defeat, Urabi retreated south of Alexandria while many of his troops stayed behind to join the mobs in their ransacking of Alexandria. Within days of their landing, the British had set up a tribunal outside the Palace of Justice on the Grand Square and to sentence those who had been involved in criminal acts. Kusel Bey, who acted as translator during the trials, made this observation. “The culprits in the case of murder were duly sentenced, tied up to trees in the centre of the square and shot, graves having been dug in front of the trees.”

British Bluejackets chasing down and arresting looters and others suspected of arson and murder. A makeshift courthouse was set up outside the Palace of Justice to convict those guilty of crimes in the aftermath of the bombardment. Illustration (L) unknown, Phot. (R) Luigi Fiorillo

One of Khedive Tewfik’s first decisions after he was restored to the palace was to dismiss Urabi as Minister of War. However, the dismissal didn’t mean much because Urabi had already regrouped with his loyal troops to form a second line of defense 30km south of Alexandria, at Kafr al Dawwar. When reinforcements arrived from Malta and Cyprus, the British sent a reconnaissance force south to test the strength of Urabi’s defenses. They found that Urabi’s troops were well dug in, and, after a month of trying to dislodge the Egyptian military leader and his soldiers the British decided to retreat and try another tactic.

Urabi would have probably held his military advantage had it not been for Ferdinand de Lesseps’ intervention. The French entrepreneur reassured Urabi that the British would never attack from the Suez Canal for fear of damaging it. Much to Urabi’s misfortune, he believed de Lesseps and decided to leave just a token force east of Cairo near Tell el Kibir to defend the capital. British commander Lieutenant General Garnet Wolseley made it known that his soldiers’ next attack would be from Ramleh, further east along the North coast. Instead, Wolseley entered the Suez Canal with a contingent of 9,000 troops unopposed and made preparations to attack from Ismailia. By the time Urabi could bolster his defenses, it was too late. Under the cover of night, British forces moved within a few hundred meters of Urabi’s front lines and attacked, catching their opponents off guard. The battle of Tell al Gibir, as it was known, only lasted a few hours during which the Egyptians and their Sudanese allies lost close to two thousand men while British losses were less than a hundred. After annihilating Urabi’s defenses, the British went on to Cairo where the Egyptian military leader surrendered officially ending the Anglo-Egyptian war.

British soldiers camped at Ramleh on the north coast. The aftermath of the battlefield at Tel el Gibir where nearly 2,000 Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers were slaughtered while defending Cairo. Phot. unknown

Urabi and his top lieutenants were tried in an Egyptian court which, instead of sentencing them to death or prison, decided to send them into exile to Ceylon. In 1901, under Khedive Abbas II, they were allowed to return. Urabi spent the last decade of his life in Egypt.

The Anglo-Egyptian War consolidated Britain’s position in Egypt. The country became a British protectorate, though officially under Ottoman governance, and remained as such for 40 years. Although Egypt gained independence in 1922, Britain still maintained a strong presence, particularly during WWII when the axis powers were threatening to capture the Suez Canal. The British continued to influence Egypt until 1952 when King Farouk was ousted from power by a group of young officers led by Gamal Abel Nasser. The last British troops left following the 1956 Suez Crisis when Gamal Abel Nasser nationalized the canal.

Well done!