By Norbert Schiller

Introduction:

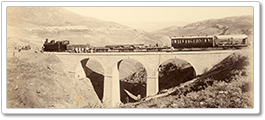

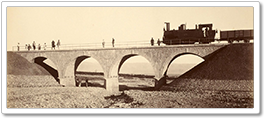

August 2020 marked the 125th anniversary of the Beirut to Damascus railway. The opening of the route for narrow gauge trains finally allowed for goods and passengers to travel between the two capitals in a record time of nine hours. The railroad, which was constructed at a time when the Beirut port was under expansion, solidified the status of the Lebanese capital as home for the main shipping hub in the region.

Before the 1895 inauguration of the train route, the two cities had been connected by a macadam, or road made of compressed stone, built by the French in 1863. The road itself had been considered a breakthrough for many reasons. First, it shortened the journey from two to four days to a total to 12 to 15 hours. Second, it made the trip safer as the caravans that crossed the treacherous mountain pass carrying supplies on donkey, mule, or camel back were at the mercy of bandits and other perils. Last but not least, the macadam opened up the interior of the country allowing agricultural goods to be traded between the fertile Bekaa Valley and the coastal regions. Besides facilitating trade, commerce, and tourism, the road established Beirut as the economic and trade capital of the eastern Mediterranean. Nevertheless, the land route had its limitations. The narrow passage was only fit for horse-drawn stagecoaches, omnibuses, and carts which stopped at relay stations where the horses were fed and replaced as the journey was too long to be completed in one stretch. It was only a matter of time before the introduction of a more efficient mode of transportation linking the two capitals which was the railway.

The checkered black and white line shows the train route between Beirut and Damascus which was inaugurated in 1895, while the two red lines delineate the road between the two cities.

The building of the railroad between Beirut and Damascus also coincided with the construction of Beirut’s new port. The two projects would work hand in hand at securing Beirut’s rise to becoming a major port city and regional hub. However, as is the case for all grandiose projects, economics and geopolitics played an important role in shaping the history of the railroad. Initially, the British were planning to build their own rail line connecting the port of Haifa in Palestine to Damascus. Fearing competition from the British, whose initiative would make Haifa the region’s premier port, the French went into overdrive to secure the funds needed for this mega project from French, Belgian and wealthy Beiruti investors. At the same time, Paris was able to obtain the concession from the Ottoman sultan to build the project. Four years after construction began, the first train made its inaugural journey and work on the new port was completed.

In the spring of 2020 Zina Hemady, Naji Boutros, Nabil Abou Khaled and myself set out on foot to retrace the route that the train took from Beirut over the Mount Lebanon range to the Bekaaa Valley. Parts of this journey are illustrated with historical images alongside my own photographs.

I would like to give special thanks to Elias Maalouf, founder of the NGO Train Train and its current president, Carlos Naffah for their contributions; artist Tom Young for the use of his painting and the late journalist and historian Samir Kassir for writing the quintessential book about Beirut’s history Beirut, from where some of the information for this piece was sourced.