Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

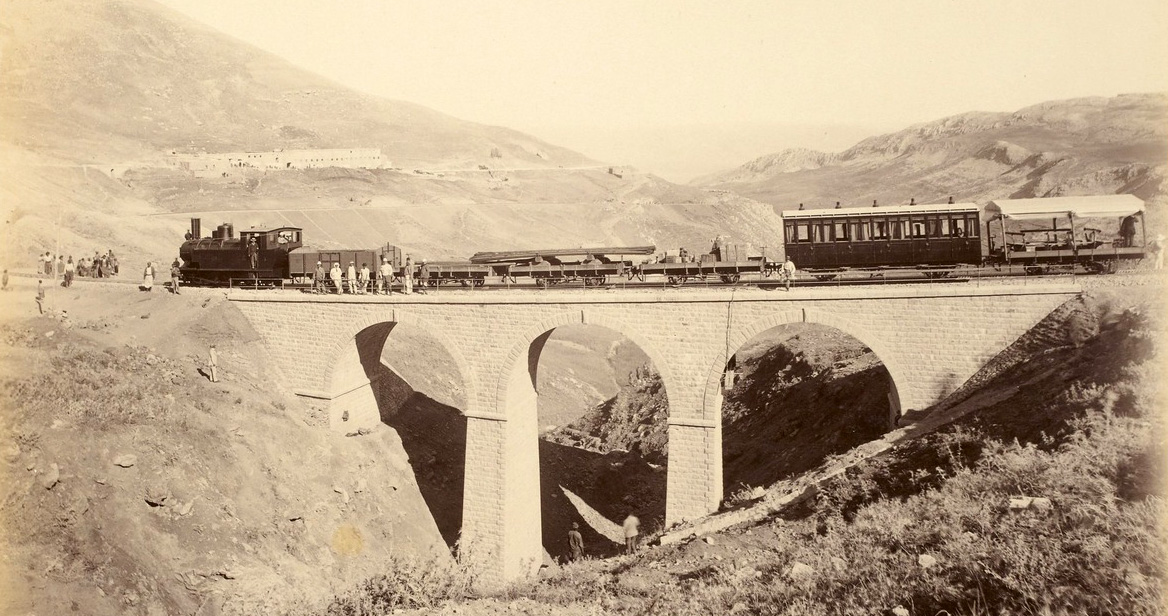

The Beirut to Damascus railroad was inaugurated on 3 August 1895 making it the first railroad to operate in the Levant. The 147-kilometers line had to overcome numerous obstacles, not least of which was crossing over two mountain ranges. However, the railroad would meet its greatest challenge 80 years after its inception, with the onset of Lebanon’s civil war in 1975. Within the first year of the war, the trains stopped operating, and, with time, the entire railway fell into total disrepair.

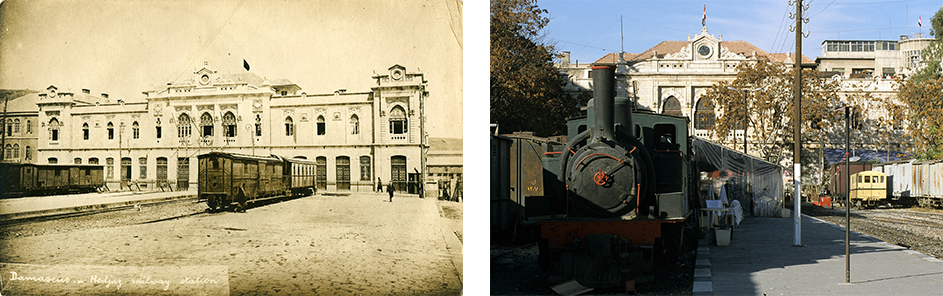

The Damascus station of the Hejaz Railway in the early 1900s. The same railroad station in 2002. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection

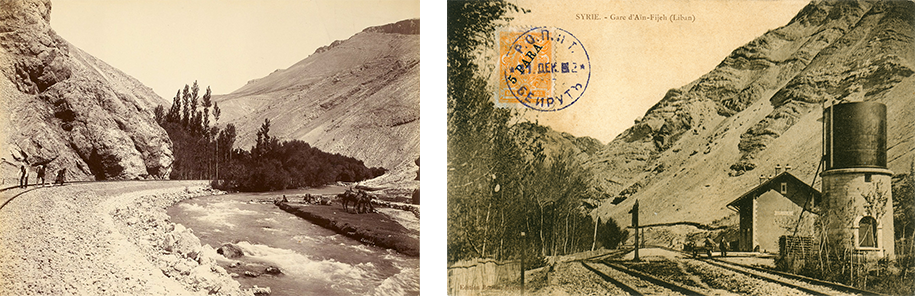

Almost three decades after the railway’s inaugural trip, the American adventurer and travel writer Harry A. Franck road the train from Damascus to Beirut describing what he saw along the way. In The Fringe of the Moslem World (1928), where Franck writes about his travels in the Middle East, the American writer paints a picture of the landscape along the Barada river and Ain al Fijeh, the main source of water for Damascus, both of which mark the beginning of the journey. “At 8:30, Ain Feegee, source of the potable water of Damascus. Here it flows into the Barada, main supply of the ancient city, up which we come all this way. Mountains on either side; groves of poplars. Many passengers left us here; had come up, perhaps, for a good drink. Plenty of room from then on; six in our compartment built for ten.”

From Damascus, the railway follows the Barada River until the station of Ain al-Fijeh, the source of water for Damascus. Phot. (L) Bonfils, Elias Maalouf Collection, Phot. (R) Norbert Schiller Collection

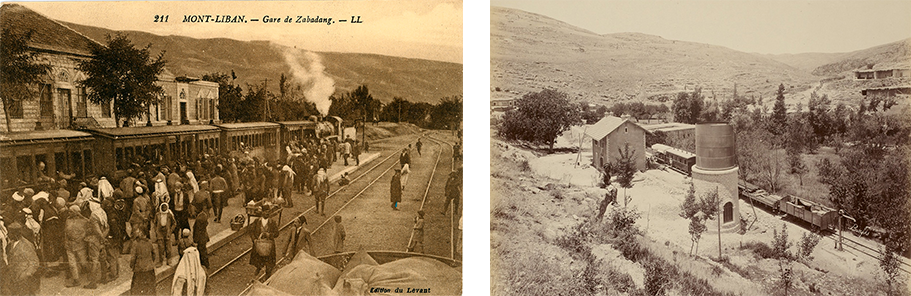

From Ain al-Fijeh, the train continued to the town al-Zabadani which sits at 1500 meters above sea level. Under the French mandate, the town was turned into a summer resort and continued to serve as a vacation spot catering to Syrian and Arab tourists fleeing the summer heat of the lowlands until the beginning of Syria’s civil war in 2011.

Crowds gather at the station of al-Zabadani which became a resort town under the French mandate. An image from 1895 shows the station of Yafufeh, the first stop after the train crosses into Lebanon. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection. Phot. (R) Bonfils, Elias Maalouf Collection,

After Al Zabadani, the landscape opened up to wide vistas with a few sparsely populated villages scattered amid the barren scenery. The small stations along the way before reaching Rayak, were functional stops intended for powering the steam locomotive engines, rather than for passenger use. “Rather arid, almost completely bare mountains, thinly scattered with mud-and-stone villages. Perfect protective coloration; they blended not only in hue but in texture with the surrounding landscape,” Franck writes in his description of this part of the journey. “Women in gay colors squatting on the flat roofs. A narrow, ever lower gorge below, filled with densely green trees, mainly poplars, in contrast to the rest of the bare scenery. Broad vistas: almost perpendicular patches of thin planting; and above masses of rock, among which, through one tunnel, we climbed, leaving all vegetation even all flocks, below,” he adds.

The station at Rayak in the early 20th century. Empty warehouses and rusted derelict trains are all that remains in this once bustling Rayak train yard. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection.

Continuing along the gorge, the train reached Yafufeh, the first Lebanese station from where travelers caught their first glimpse of the Bekaa Valley, the vast fertile plain separating the Mount Lebanon and anti-Lebanon mountain ranges. “Yahfulah at 10:30 ended the Damascus-ruled division of the country; began the Grand Liban tributary to Beirut,” notes Franck. “A broad fertile plain between the two ranges of the Lebanon, punctuated by the junction at Rayak, with the (train) line to Baalbek and the north.” Franck makes a special mention of the food and drink served at Rayak, which must have come as a relief to a Western traveler. “A dining-room here, with a French dinner of Syrian ancestry for about 40 cents, fair wine included.” The French menu must have been a fairly new introduction after the beginning of the French Mandate in the early 1920s. A previous traveler and writer, Albert Bigelow Paine, who stopped at Rayak in 1909 describes a more traditional culinary experience. “…there is a lunch-room there—a good one by Turkish standards. It was our first complete introduction to Turkish food—that is a diet of nuts, dates, oranges, and curious meat and vegetable preparations.”

Besides its train station and restaurant, Rayak was home to the largest train repair yard in the region. There were warehouses full of spare parts and technicians who could work on trains powered by steam, coal, and fuel. It was only natural that during WWII the train yard would be converted to a repair center for French fighter planes and weaponry. Presently, 45 years after the beginning of Lebanon’s civil war, the train yard has been reduced to a ghost town with abandoned warehouses, rusted train engines, and train cars chocked by the wild vegetation covering the entire area.

The station at Ma’allaka when it was first built in 1895. Today, a hospital has replaced the train station and all that remains is the water tower. Phot. (L) Bonfils, Elias Maalouf Collection.

From Rayak, the train continued across the Bekaa Valley stopping at Ma’allaka. Unfortunately, this station has all but disappeared after it was torn down and turned into a government hospital named after Elias Hraoui, who became president in 1989 just before the end of the Lebanese war. All that remains of this historical landmark is the water tower. After Ma’allaka came Saadnayel, which, contrary to its predecessor, has been preserved thanks to local government efforts. The site has been turned into a public garden and outdoor museum housing the restored station as well as one of the original trains.

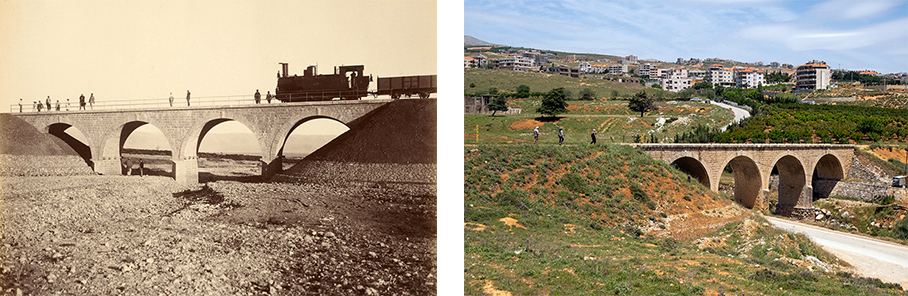

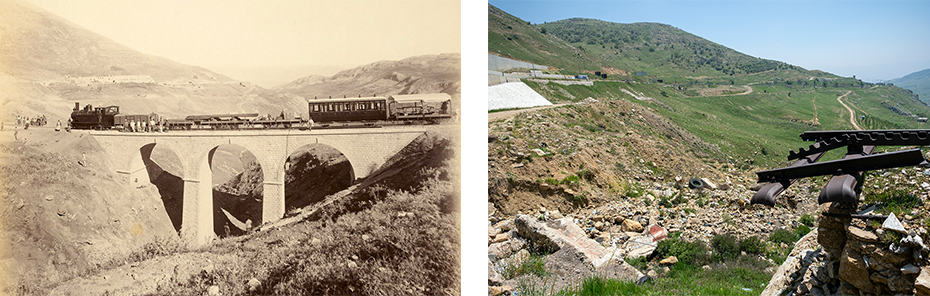

Climbing the foothills above the town of Saadnayel, the train crosses the Djellala Bridge. Today, the river that once ran below the bridge has been replaced by a road. Phot.(L) Bonfils, Elias Maalouf Collection.

After Saadnayel the train turned westward slowly climbing out of the valley and into the foothills of the Mount Lebanon mountain range to Jditah-Chtaurah. Lebanon’s turbulent history has also taken its toll on the station at this location. With no effort to salvage what little remains of this structure, like many others along this route, Jditah-Chtaurah will most likely collapse. From there the route becomes steeper, and, for the first time since climbing out of Damascus, one can notice the steel teeth running in the center of the tracks allowing the train to grip as it climbs. Sadly, most of the tracks were ripped out during the war to either be sold for scrap metal or used by militias and invading armies as barricades.

The train making its way up the mountain. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection

The Khan M’rad bridge built in the late 19th century near the summit. The bridge was destroyed around the end of Lebanon’s civil war. It was stipulated that the structure was purposely destroyed to protect Syrian truck companies from competition from the railroad. Phot. (L) Bonfils, Elias Maalouf Collection.

As the train continued to climb up the mountain, it entered into a tunnel carved into the rock to avoid going over the peak. For a passenger riding the train in the early 20th century, traveling through a dark tunnel surrounded by rock on all sides was an ominous experience. “Then the train climbs up the edge of the mighty chasm until we are lost in the clouds. Though May has begun, it is still cold and miserable up here,” writes Franck. “A long tunnel—and no lights in the train. But passengers have matches and candles, should anyone be bold as to start any sheik stuff (stealing),” he adds. “That is the trouble with trains: they never go over the top. Get near the climax and then suddenly dodge it, by darting into a black, smoke-and gas-filled hole, to come out upon quite another problem, without any indication of how this one was solved.”

Nearing the summit from the East is a series of cement tunnels which were built in the 1930s to protect the tracks from snow accumulation. (Phot. (L) John Knoweles, Elias Maalouf Collection.

The trip in the other direction, however, seems to have left a different impression on the American writer Paine in 1909. As the train exited the tunnel, it came into full view of the breathtaking snow-capped Mount Hermon, Jabal el Sheikh, rising majestically above its stark surroundings. “Look, there is Mount Hermon! And sure enough, away to the south, through nigh upon us it seemed—so close that one might put out his hand and touch it, almost—there rose a stately, snow-clad elevation which, once seen, dominated the barren landscape,” wrote Paine. “It was so pure white against the blue—so impressive in its massive dignity—the eye followed it across the vista, longed for it when immediate peaks rose between, welcomed it when time after time it rose grandly into view.”

The station at Dahr el Baidar summit. Phot. (L) John Knoweles, Elias Maalouf Collection.

Cement tunnels were built in the 1930s near the summit to protect the train from deep snow. Phot. (L) John Knoweles, Elias Maalouf Collection.

On the western side of Mount Lebanon, the train descended through a series of tunnels which were erected in the 1930s to protect the tracks from snow accumulation. The first stop on this side of the tracks is Ain Sofar, once famous for its Grand Sofar Hotel, built in 1892, to cater to the rich and famous of the Arab world. Today, the hotel lies mostly in ruin and is resurrected ever so often to host an art exhibition and or musical performance.

The station of Ain Sofar back in its heyday alongside what it looks like today. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection

From Ain Sofar, the train continued its downward journey passing mansions that once belonged to the Lebanese elite who fled to Sofar to escape Beirut’s stifling summer heat. Today, these once glamorous homes have been taken over by Syrian families fleeing civil war in their country.

After descending through open country filled with flowers and pine trees, the train arrived at Bhamdoun. Many of this summer resort town’s mansions and apartment blocks lie empty, as a stark reminder of the brutal Mountain War which was fought between Druze and Christians in 1983. But in its heyday, Bhamdoun was a bustling vacation spot attracting visitors from all over the region. Franck, who also walked around the world in 1904, had made a stop in Bhamdoun on his first journey. When he returned two decades later to take the train trip, he was amazed by the changes he witnessed. “Bhamdoun is now one of many big, bustling, red-roofed modern towns catering to summer colonists, and no longer has the slightest interest in a wandering faranchee (foreigner). There is little of that naïve, hospitable friendliness of 1904 left in the Lebanon, anywhere in Syria, now. Hotels and other fine things have killed it.”

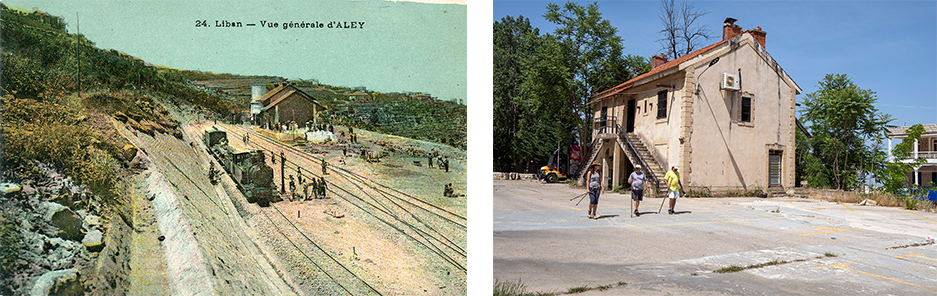

The train enters the town of Aley in the 1940s alongside of what the route looks like today. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection

From Bhamdoun, the train wound its way down to the town of Aley. Today, the station is still relatively intact as it is used as a government office, while the water tower has been turned into a bar/café. However, there is nothing left of the tracks in Aley due to illegal buildings and other construction on property that still belongs to the Railway and Public Transportation Authority. From Aley, the train was unable to continue forward due to the angle of the mountain, so it had to go in reverse to the next station at Araya. “Now the train turns around or backs up—goes, at any rate in the opposite direction—and suddenly the Mediterranean appears,” writes Franck describing this portion of the journey. “Beirut, like a queer shaped stain on the edge of the sea, towns in hollows, a half wooded plain degenerating into a stretch of sand, so far below that it looks like another world.”

An image of the Aley station from the early 20th century. Today, the station of Aley is used as a government office. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection

The station at Araya in the 1960s. Today, the station is covered in vines and has fallen into disrepair. Phot. (L) John Knoweles, Elias Maalouf Collection.

From Araya, the train proceeded down the mountain to Jamhour. Unlike the other abandoned stations on the rail so far, this one is actually inhabited by a former railway employee and his wife who have converted the building into their private residence. The couple is suspicious of outsiders who show interest in the train and its history as they are obviously living in the station illegally. But because of rampant government corruption, and the more pressing gargantuan political and economic problems that the country is facing, squatters like this couple and land developers have been able to chip away at the little that is left of this once thriving rail line.

The station at Jamhour as it was in the 1910s compared to today. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller Collection

As in Jamhour, the station at Baabda is illegally occupied. The metal rails are still visible around Baabda and one is able to follow them for a short way in both directions. However, the foothills above Beirut are so build up that after a short walk the train’s path simply disappears into a concrete jungle. In 1927, Franck describes a very different scenery at this very spot. “Up here, cedar groves and red-tiled homes and much greenery; down there a subtropical land, half seen through a haze that resembles murky water. The train goes forward again, as if it were tired, like a playing child, of backing up,” he remarks. “Down, down, down, to the orange groves, to palm-trees, to a caressing air quite unlike that of the highlands, and on across a great green, tree growing plain, with many modern red-roofed houses, of stone, and evidently a more advanced population—if comfort and luxury are progress,” he continues lamenting what seemed like rapid urbanization back then.

The Baabda station in 1895. Today, laundry hangs in the yard surrounding the station as a sign that it is illegally occupied. Phot. Bonfils, Elias Maalouf Collection

The final two stations before the terminus at Beirut are Hadath and Furn el Chebbek. Both structures are in ruin and almost impossible to find. The rail lines have been eaten up by the city’s unrestrained growth since the end of the civil war. Haphazard construction and a mishmash of roads going in all directions have erased any trace of the rail network that once connected Beirut to Damascus, as well as the coastal rail line that ran between Naqoura in the south and Tripoli in the north.

The Hadath station in the early 1970s as compared to now. Phot/ (L) Elias Maalouf Collection

While the Hadath station is uninhabited, the land around it is used as an overflow parking area for a company that owns the adjacent property. The station has fallen into complete disrepair and is covered with vegetation. Trying to retrace the direction of the tracks is almost impossible because of all the new construction surrounding the station.

The central Beirut train station alongside a postcard showing the inauguration of the train station built at the port in 1903. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

Lebanon is full of pre-war landmarks that are now only visible to those who witnessed their past glory. The Beirut-Damascus railway is one of these relics that is in danger of complete disappearance if it continues to be ignored and violated by those seeking to profit at any cost while the country continues to be mismanaged by a callous ruling elite. Whatever its fate, this rail line will continue to live through pictures, travel narratives, and local lore passed on from one generation to another.

Great then & now comparisons.

And for me an annoyance at myself for not having rode there in 1962. Had the railroad staff talk me out of this trip.

Greetings

Klaus Matzka

Vienna, Austria

The golden Era of Lebanon until the Civil War.. Badly we don’t know how to preserve our historical cities. And culture