By Norbert Schiller

In February 1896 a French tourist and early amateur photographer boarded the steam ship Le Niger traveling from Marseilles to Alexandria, Egypt, via the straits of Messina. The first photographs he took on his voyage were of fellow passengers lounging around the ship’s bow. Technically, these images were well composed, an indication that the traveler had experience using the camera. However, as the ship made its way through the Strait of Messina, dividing Sicily from the mainland, the photographer’s technique begins to reflect his amateur background. As the tourist attempts to capture land on either side of the strait, he instead produces images depicting mostly water with barely a hint of the mountains rising out of the sea far off in the distance. For decades, similar photos were taken by tourist from the decks of ships as they passed landmarks such as the Rock of Gibraltar or the island of Malta. Such images made for great memories, but poor photographs due to those early cameras and their lenses which did not have the focal length required to capture objects far off in the distance. It wasn’t until the 1930s, with the proliferation of the 35mm camera, that the telephoto lens become accessible and practical to use.

Steerage passengers on Le Niger mingling at the bow of the ship. The Italian town of Messina photographed while transiting through the Straits of Messina. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

After the Straits of Messina, the next land sighting was the Egyptian Mediterranean city of Alexandria. Typically, after arriving in Alexandria, most tourists booked the rest of their Egypt tour through the British travel company Thomas Cook, which had a monopoly on luxury boats traveling up the Nile from Cairo to Aswan and Wadi Halfa. I can only assume that the tourist in question did not stay long in Alexandria because he only took two pictures in this fascinating and photogenic city. The first image shows a funeral procession in a poor part of the town, while the other is of a man dressed in rags sweeping a walkway in a garden.

A funeral prosession in a poor part of Alexandra. A street sweeper clearing a walkway. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

In Cairo, in those days reached by train from Alexandria, the traveler took images of royal palaces, a mosque, and another funeral procession near el Hussein, in an overcrowded part of the city. He also visited the Giza plateau, but ironically didn’t take pictures of either the pyramids or the sphinx, two of Egypt’s the most documented landmarks. The Frenchman did, however, include a photo of a European man, most likely the photographer himself, and his guide posing on their donkeys before riding off to the Pyramids. The caption below the image reads départ pour les pyramids. The exclusion of the pyramids from this album was a mystery that was solved when an interesting thread started emerging in this photographic journey.

The courtyard of Mohammed Ali Mosque. A photograph showing what is most likely the French tourist and his guide at the Giza plateau. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

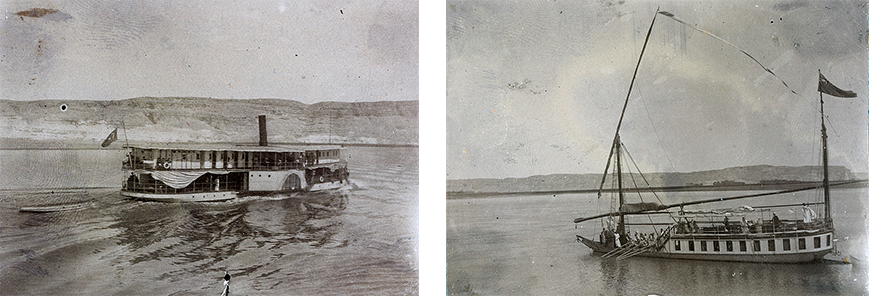

The rest of the photos document the voyageur’s trip up the Nile. Up until the 1870s, the only option for touristic travel to Upper Egypt was on a traditional dahabiyyah sailboat which took three months, or sometimes longer, depending on the wind. By the 1890s, Thomas Cook had started offering a second option, a 20-day round-trip excursion on a luxury steam paddleboat. The French tourist, who chose the quicker option, spent the next three weeks traveling on the steamship Rameses to the First Cataract, just above Aswan, and back.

A tourist steam paddle boat that takes 20 days to go up to the First Cataract and back. A traditional dahabiyyah sailboat takes three months, and sometimes longer, to make the same trip. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

Although the Rameses made several stops during this journey, there are few photographs in the album of the sites along the way. The available images are of other steam paddleboats plying the Nile waters and village scenes captured from the deck of the steamboat. Even when the Rameses stopped at the glorious ancient tombs of Beni Hassan and the Temple of Dendera, the photographs were taken from on board the Rameses. In Beni Hassan, the tourist captured the chaos on shore as donkey drivers crowded at the end of the gangplank to take the foreign visitors to the tombs, while at Dendera he photographed a falouka (sailboat) that ferried villagers back and forth across the Nile. It wasn’t until the Rameses reached Luxor that the Frenchman took his camera off the boat only to photograph Luxor Temple, which would have been right beside the docking area. He did not take his camera to Karnak or any of the other magnificent temples on the West Bank of the Nile. This is where I started viewing this photographic expedition with a 19th century lens, which would lead to the answer to my nagging question.

A shadouf used to raise water from the Nile to irrigate the fields. A young boy from the Bisharine nomadic tribe standing beside railroad tracks. The columns at Luxor Temple. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

Between Luxor and Aswan, the Rameses stopped at three places known for their temples, but only took pictures at Kom Ombo where the ruins were next to the boat landing. At Esna and Edfu there were two pictures respectively depicting children swimming in the Nile and a group of locals sitting on the banks of the Nile. All three of these photographs were taken from the deck of the paddle steamboat. When the Rameses reached Aswan, the images show the shoreline and Elephantine island both taken as the boat sailed by. There was also a photograph of a young boy from the Bisharine nomadic tribe, that roams the very southeast of Egypt, standing alone on the railroad tracks. I suspect that this was taken near a boat landing.

Egyptians sitting near the boat landing in Esneh. The temple of Kom Ombo. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

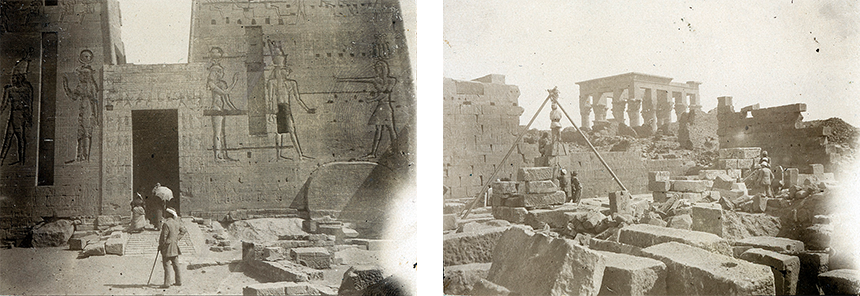

At this point, one would think that this visitor had no interest in the archaeological wonders of Egypt but was more drawn to scenes of daily life which he could photograph from the comfort of his boat. However, when he visited Philae Temple, just above Aswan, the traveler included five photos in the album, the greatest number so far from any of the sites he had visited. What distinguishes Philae from any other temple in Egypt is that it is located on an island, and, like Luxor Temple, it is located close to a boat landing. At every other site where the Rameses had docked, the traveler would have had to ride donkeys to visit the ruins. Herein lies the key to the mystery. My hunch is that this tourist didn’t want to risk damaging his camera by taking it on a donkey excursion, preferring to leave it behind on the boat. That’s the only plausible explanation to the documentation in this 1890s photo album.

Victorian tourist at Philae Temple. Archeologists and Egyptian workers moving large stones. at Philae Temple. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

After Philae, the next three photos were taken downriver at the First Cataract (rapids), the last stop in this visitors’ journey to Upper Egypt. Besides the general views of water rushing over the rocks, there is a perfectly timed photograph of a young man in midair captured as he jumped off a rock into the water. From there, the boat made its way back to Cairo. At this point, the photos consist mainly of the Rameses docked at different ports and of tourists lounging on the deck. There were also photographs of dahabiyyahs, sailboats ferrying agricultural goods, and locals operating the shadouf, a contraption made of buckets and pullies used to elevate water from the Nile to the fields for irrigation.

The First Cataract. The photographer catches a young man in mid air jumping into the water. Norbert Schiller Collection

Back in Cairo the French traveler ventured into the streets capturing scenes that are challenging even in today’s standards, and which would not have been possible before the introduction of the hand-held camera. He photographed Khedive Abbas II, the ruler of Egypt, attending military exercises then followed his convoy, negotiating around crowds and horsemen, to come into close proximity of the khedive and snap his picture in an open carriage. The traveler also photographed what seems like Friday prayers at a mosque courtyard.

Khedive Abbas II being escorted through the Streets of Cairo after attending a military ceremony. Moslems during Friday prayers. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

The last image from Egypt is taken from the window of a room at the Shepheard’s Hotel in the center of Cairo. Judging from the angle of the photograph, it’s obvious that the guest had a room in the front of the hotel overlooking Ezbakeya gardens and the Cairo Opera House. This picture wraps up the Egypt part of the album, which ends rather abruptly before the traveler resurfaces in Venice.

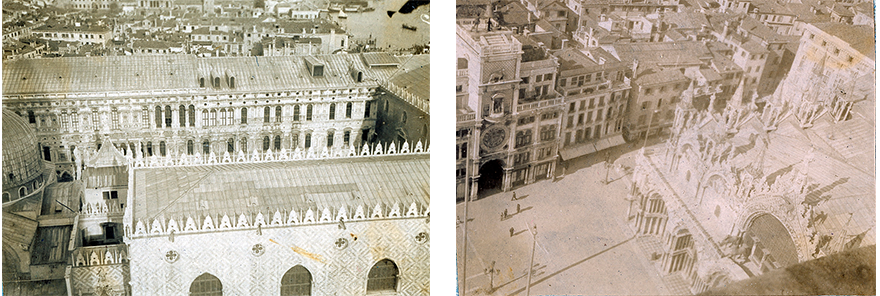

Pictures taken from atop the bell tower of Doge’s palace and San Marco cathedral. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

The first pictures in Venice consist of an overview of the city taken from the iconic bell tower above Piazza San Marco. The images show the square, the San Marco church, Venice port, and Doge’s palace, a Gothic-style palazzo which has become a Venetian landmark. Before the invention of the handheld camera, such images would have been an incredible feat considering that the photographer would have had to carry the equipment up to the top of the tower and set it up in that location. Moreover, the handheld camera gave this tourist the freedom to lean over the rails and take photographs directly below him, which would have been nearly impossible before this technological breakthrough.

Ponte di Rialto, the oldest bridge spanning the Grand Canal and Ca d’Oro palace. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

After taking a few more shots of the area surrounding Piazza San Marco and of the Doge’s palace, the visitor hired a gondola to tour the canals. During his ride he captured the Grand Canal, Piazza San Marco, Ponte di Rialto, the oldest bridge spanning the Grand Canal, and passenger transport ships in the Venice harbor. He concludes his album with photographs of gondolas taken from the shore.

The Grand Canal and Piazza San Marco. Phot. Norbert Schiller Collection

This photo album gives great insight into the world of early tourist photography. Before the introduction of the handheld camera in the 1890s, travelers purchased professionally-made albums with large prints as a memory of their journey. Until then, only professional photographers and serious photo enthusiasts had the incentive to carry a camera, large glass plates, and developing chemicals with them on their travels. This photo album, compiled by a tourist who snapped his own photos, is one of the first prototypes of a travel scrapbook. Since handheld cameras had a high price tag at the time, this traveler would have taken extra care not to damage his precious equipment. Therefore, I can only assume that, like other Victorian travelers, this tourist would have purchased a professional album documenting the sites he encountered on his visit, while using his camera to photograph scenes that captivated him.