by Zina Hemady

From Nablus we descended into the Jordan Valley, zigzagging through Palestinian villages and Israeli settlements, many of which have been the sites of vicious attacks and reprisals in recent years. However, even in these bloodied lands, there were moments of escape into history and nature when admiring a spread of countryside from a Roman outpost, clambering over rock in a gorge that has served as a refuge for wildlife and revolutionaries alike, or spending the night with a Bedouin clan in their desert camp. In Jericho, our experience became less exclusive albeit fascinating, as we toured sites that have attracted visitors since the nineteenth century, the days of early travel to the Holy Land.

A view of Nablus surrounded with agricultural fields taken from a location south of the city. A photograph from the 1920s showing cultivated lands around Nablus. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Karl Gröber

Heading out of Nablus, we were turned back at the Israeli checkpoint in Huawara, most likely due to an explosion on a Jerusalem bus the previous day. This gave us a faint glimpse into the daily tribulations of Palestinians who invariably feel the ripples of every attack against Israel or its citizens, whether they are involved or not. We then drove to nearby Awarta, a prime example of a community that has suffered collective punishment since 2011, when two of its youths were convicted of killing a family in the settlement of Itmar. The incident, however deplorable, came within the context of over a decade of settler harassment and deadly attacks against residents of Awarta and nearby villages, still common occurrences today. We then headed to the Roman fort at Jabal Urmah (Mount Aurma) which, at an elevation of 800 meters, offers a breathtaking view of rocky terraced hills and agricultural fields. Underneath the fortress are underground rooms carved into the rock which were used to store supplies during long periods of siege.

Still in a historical time warp, we walked down from this wind-swept hill to the village of Aqraba which has been identified as the biblical site of Akkrabim. Ruins and artifacts from various historical periods have been discovered here, but excavation efforts are slow. The most notable discovery is that of stones covered in Greek inscriptions, believed to come from a 5th century Byzantine church, which have been used in the building of the town’s main mosque. In Aqraba, which is economically depressed due to its proximity to Israeli settlements, land loss, and emigration, the only booming business is that of car theft from Israel. However, there are some efforts to promote less illicit entrepreneurial initiatives. The women’s association, where we ate lunch, is a local NGO that receives international funds to support small businesses run by women seeking to gain some financial independence.

The view from an escarpment overlooking the Jordan Valley in 1904. A similar view taken during our hike. Phot.(L) Norbert Schiller Collection, (R) Norbert Schiller

After Aqraba, we trekked through wheat fields and olive groves, a landscape that became increasingly barren as we approached the edges of the Jordan Valley (Wadi el Ghor). Emerging from the fields, we encountered Route 505, one of the contested bypass or “apartheid” highways that have been carved out in the West Bank to exclusively accommodate the settlements by linking them with the coast. Dodging settler buses and military vehicles, we made it to the other side and continued our walk along an escarpment from where the Jordan Valley, 800 meters below sea level, came into full view. From the agricultural plains rise the valley’s dry bare mountains behind which the river and the hills on the Jordanian side are a mere haze.

We continued our climb until we reached the village of Duma, previously an obscure quiet hamlet in rural Palestine. However, Duma made headline news nine months before our visit when two settlers fire-bombed one of the houses killing a couple and their 18-month-old infant. When we arrived in the village, residents were preoccupied with the recent arrest of the female victim’s brother, due to his alleged connections with Hamas. I asked our hostess Nihal, a mother of five, if she feared for her family’s safety, considering the village’s vulnerability in the midst of so many settlements. Nihal looked out at the lights shining from nearby Migdalim and shrugged saying that living with fear was her village’s predicament.

Wadi Auja just before it enters the Jordan Valley. Circa 1910s. Walking through Wadi Auja to the Jordan Valley. Phot.(L) Norbert Schiller Collection, (R) Norbert Schiller

The following morning we embarked on the most unique experience of the entire journey as we descended through Wadi Auja, a secluded gorge rich in flora and fauna, historical sites, and peculiar landmarks with special significance to the locals. The hike started at Ain Samiya, one of the West Bank’s most abundant springs which supplies the city of Ramallah. However, before the spring’s waters were diverted, they used to flow down the Jordan Valley carving this spectacular canyon in their wake. After walking through fields of thorn scrub and briefly stopping under the shade of a Ziziphus spina christi tree, commonly known as Christ’s thorn, we began walking down the limestone rocks and boulders that line the dried up streambed. We spotted goats climbing the wadi walls and colorful butterflies flitting among the wildflowers, the most spectacular of which were the holy hocks with their tall erect stems and hefty pink flowers.

Walking on the edge of the Jordan Valley towards Jericho. A camel caravan crossing the Jordan Valley. Circa 1900s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) Underwood & Underwood, Norbert Schiller Collection.

As we descended towards the valley we felt the climbing temperatures, but Nedal continued to entertain us with stories from his homeland keeping our minds off the heat. He pointed to a pond called Maqtal el Badawi, or Death of the Bedouin, and told the tale of the shepherd who drowned there. Mgharet Sabha, Sabha’s Cave, is one of many small openings in the sides of the gorge where a local woman chose to lead a hermit’s life. The most interesting site was Oum el Khafafeesh, the Cave of the Bats, where Marwan Barghouti, a dangerously charismatic Palestinian activist hid during the second Intifada, which he is believed to have led. However, feeling too isolated he ventured out and was immediately captured by the Israelis. Barghouti remains securely behind bars as his freedom would constitute a threat to Israel as well as the Palestinian leadership. At the bottom of the wadi, where it opens up to the Jordan Valley, is the bubbling spring of Ain Auja where we splashed and took dips in an attempt to revive ourselves after this intense trek.

A bedouin camp near Jericho with tin-roofed sheds, alongside a 19th century photograph of a Bedouin camp in the Achor Valley north of Jericho. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) Bonfils, Norbert Schiller Collection, Bonfils

As the sun started setting, and the desert light turned from stark white to more demure shades of purple and blue, we arrived at the desert camp of the Abu Kharbeesh clan. The tribal chief’s wife Oum Nayef greeted us and, as we rested on the mats laid out under the huge tent, she updated Nedal on the latest news. Her husband had kidney failure and required dialysis, an expensive treatment which is draining the family. At the same time, Israeli authorities are threatening them with eviction for the second time. Since 1967, Bedouin tribes have been frequently relocated to the worst lands, away from water sources as the government appropriated their lands turning them into military zones or settlements. Since they have lost access to their large pasturelands, many Bedouins, including members of this tribe, have been forced to work as manual labor in the settlements. In spite of their troubles, the Kharabeesh have not lost their warmth and hospitality, two traditions at the core of Bedouin culture. The men prepared a meal known as Zafer, which consists of chicken and vegetables cooked underground in the Bedouin version of a crock pot where the food simmers slowly over low coals until the meat is as tender as butter. As we waited, Noujoud, 13, and her sister Shaima’, 11, invited the other woman hiker to their tent to dress her up in a traditional Palestinian embroidered dress and give her a make-over. I had the privilege of learning how to milk a goat, a task at which I failed miserably.

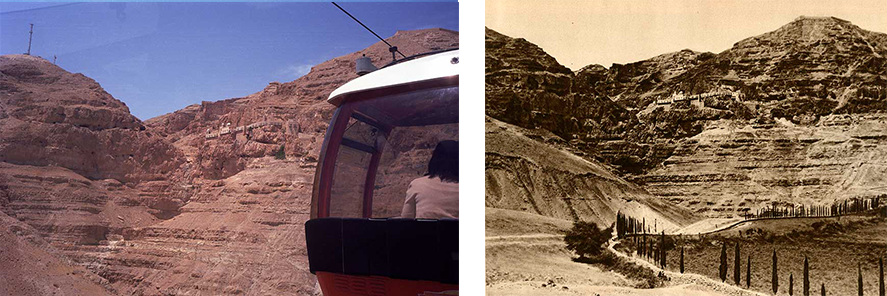

A cablecar takes visitors up to the Monastery of Temptation where Jesus was allegedly tempted by the devil. Before the cable car was built, pilgrims had to walk up a path leading to the monastery. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Karl Gröber

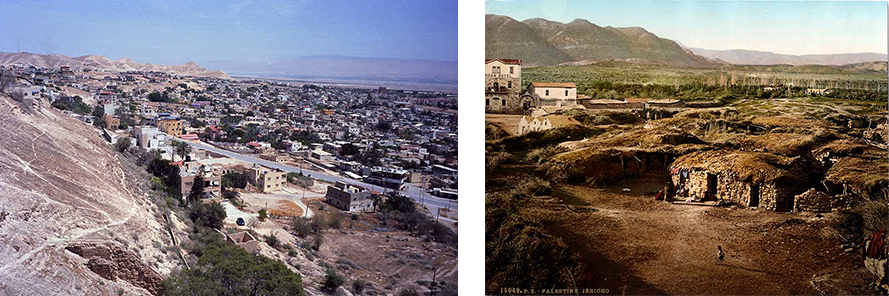

Modern-day Jericho as compared with a nineteenth century image of the city considered to be one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world dating back to 9000 BCE. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

The following day, our 7th on this journey, we walked to the nearest road and headed to Jericho by van. The city, which is over 10,000 years old, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in the world and has enough sites to justify its historical weight. Unfortunately, we only visited a select few that fit the theme of our hike. We toured the Mount of Temptation where Jesus resisted Satan after a 40-day journey in the desert. Deir Quruntal, or the Monastery of the Temptation, sits at the top of the mountain and marks the site of this biblical account. The monastery dates back to the 6th century, but after hundreds of years of neglect, it was rebuilt by the Russian Orthodox Church. The two most impressive sites in this monastic complex are the rock where Jesus is said to have stood during his face-off with Satan and a balcony that offers a magnificent view of Jericho.

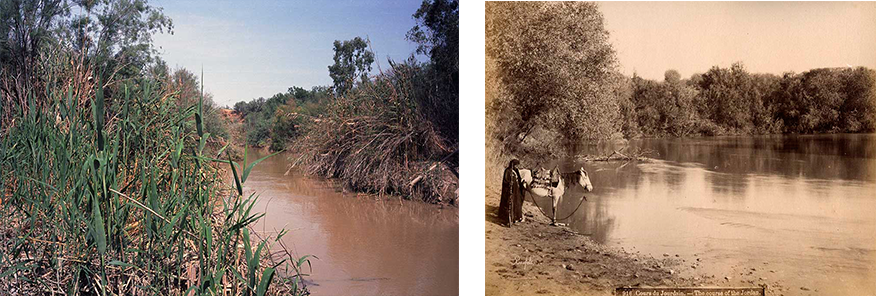

The Jordan River today is much narrower than it was in the nineteenth century as the demand for water has depleted the river’s supplies. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Bonfils

Our next stop was the River Jordan to visit Qasr el Yahud, the spot where Jesus is believed to have been baptized by John. The site was developed by the Israeli National Parks authority in 2011 and attracts thousands of pilgrims from all over the world who come here to reaffirm their faith by submerging themselves in these sacred waters. However, the mud brown color of the river suggests anything but purity and holiness. A combination of massive water extraction, pollution from pesticides and agricultural run-off, and sewage has turned this iconic river into a health hazard. Nevertheless this has not deterred diehard white-clad pilgrims from taking the plunge into these murky waters. As we arrived, a group of Russians were completing their baptismal rites under the guard of Israeli soldiers who were just as stunned by the mid-day heat as we were.

Side-by-side photographs of bathers floating in the Dead Sea approximately 140 years apart. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R) N. Schiller Collection, Luigi Fiorillo

Our last, and most anticipated stop was the Dead Sea, a natural wonder which is also a grave environmental concern. This enclosed body of water is well known for its high salt levels which allow bathers to practically sit on its surface, and mineral-rich mud that heals the skin and makes it smooth and silky. However, as the waters of the Jordan River have been diverted for agricultural use, the Dead Sea has gradually lost its main water source and is rapidly shrinking. As we drove through groves of palm trees on our way to the resort, we saw salt deposits dozens of meters away from the shore showing how much the water had receded. Nevertheless, bathing in the sea and indulging in its natural resources is still as magical as it would have been a century ago, before this corner of the world was sucked into a political and now environmental sinkhole that is pulling it closer to the bottom.