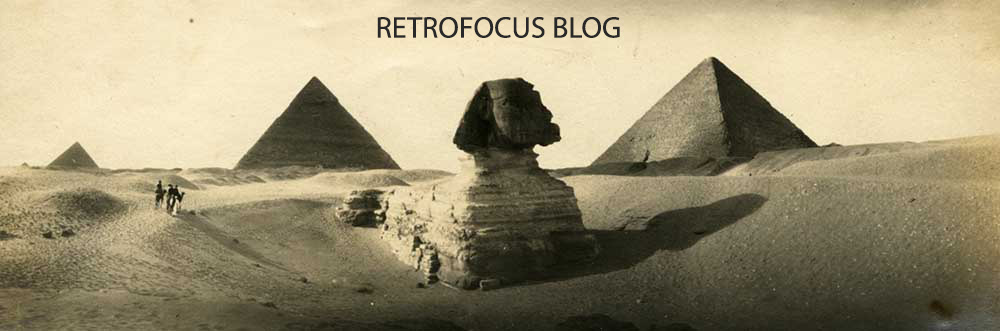

Three time world heavyweight boxing champion Mohamed Ali prays at the Mohamed Ali mosque in Cairo, Egypt on 06 October 1986. Phot. Norbert Schiller

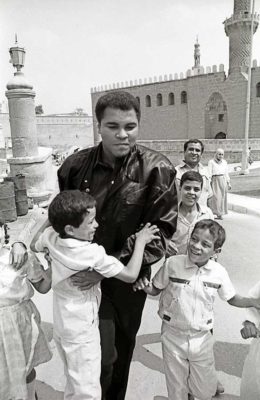

Thirty years ago I had the privilege of meeting boxing legend Mohamed Ali for the first time. It was October 1986, five years after his last fight, and he was in Cairo to make a special announcement.

I was working for the French news agency Agence France Presse (AFP) at the time. One day, I answered a call from Mohamed Ali’s press spokesman who was inviting us to the “Champ’s” suite at the Cairo Marriot Hotel. Before hanging up, the spokesman asked me to invite other members of the press corps to the event. My first thought was that Mohamed Ali was coming out of retirement and was going to announce an upcoming fight, possibly in Egypt.

I got off the phone and informed the office that we had been invited to meet with Mohamed Ali. That evening, four of us from AFP went to Ali’s suite and, to our surprise, we noticed that no one from the Champ’s entourage was present. The only other person in the room was a member of the hotel staff arranging food on a table. Not knowing what to do, we sat down and made small talk. As we waited, it suddenly dawned on me that I hadn’t called to invite other members of the press. A while later, there was a knock at the door and in stepped a colleague from Time Magazine who had also been notified. In the end, less than a dozen journalists from both the local and international media attended.

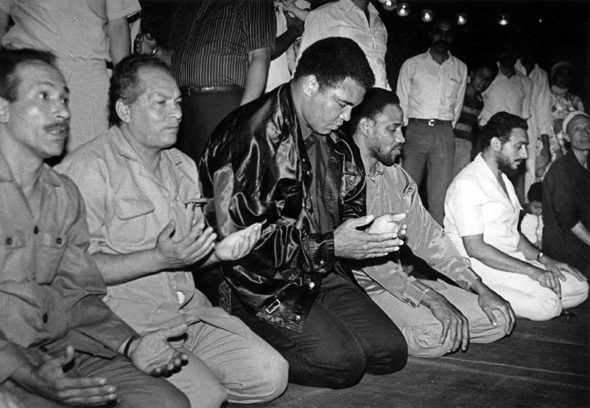

With Mohamed Ali at his Cairo Marriot Hotel suite. Phot. Michael Nelson

When Mohamed Ali opened the door he was noticeably upset when he saw so few journalists waiting for him. His press spokesperson was obviously unaware of the fact that it wasn’t a journalist’s duty to alert colleagues about a news event. After eying us suspiciously from the doorway, Mohamed Ali suddenly rushed towards the AFP sports writer, Emmanuel Maradas, who happened to be a big and muscular African, originally from Chad. Ali looked him square in the eye and said, “You look like George Forman.” Ali and Maradas shadowboxed for a while which helped dissipate the tension. Ali then passed out autographed photographs of himself and books about Islam, which he dedicated to each one of us. Instead of making any formal announcement, Ali decided to have fun. He posed for pictures and played mind games, like the one where he appears to be levitating, while his feet are still firmly on the ground. After an hour of vintage Ali entertainment, we all left.

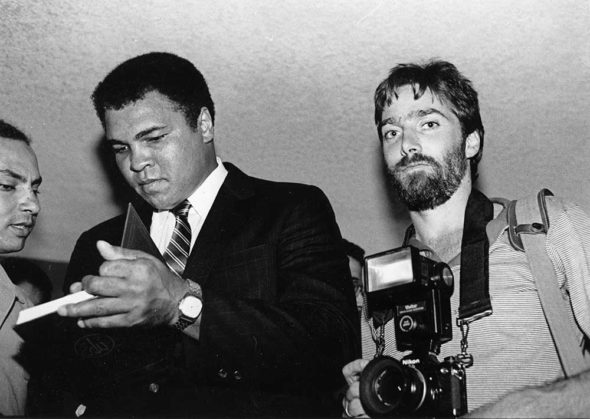

Mohamed Ali mingling with children outside the Mohamed Ali mosque overlooking Cairo. Phot. Norbert Schiller

The following morning Ali announced that he was going to produce a luxury car in Egypt for the Arab market called the “Ali.” After his press conference, I accompanied Ali to the Mohamed Ali mosque, perched on top of the Mokattam hill overlooking Cairo. The mosque, which bears the Champ’s name, was actually dedicated to Mohamed Ali Pasha, the founder of modern Egypt. A crowd gathered at the site as word went around that Mohamed Ali was coming for payers. The Champ stopped on his way in and mingled with his fans, in typical Ali fashion. After a few jokes, handshakes, and hugs, he entered the mosque and performed his prayers. As for the Champ’s venture into the auto industry, it was a non-starter and the “Ali” never made it past the publicity phase.

My next encounter with Mohamed Ali happened a few years later when I was in Iraq in December 1990 a few months after Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. At the time, I was working for the Associated Press (AP) and happened to be one of the few western journalists in the country. One afternoon, I bumped into Mohamed Ali in the corridor of my hotel. He was the last person I was expecting to run into, and he was equally surprised to discover a western male moving freely in Iraq in the middle of a hostage crisis that he was trying to solve. Ali was one of few dozen peace brokers who flooded to Baghdad to secure the release of western male hostages or “human shields” held by the Iraqis to protect military and other sensitive installations from potential bombing by the U.S. and its allies. Iraq was essentially buying time to ready itself for the inevitable showdown with the western-backed coalition.

Mohamed Ali arrives in Baghdad to secure the release of western hostages. Phot. Norbert Schiller

In an attempt to appeal to the growing antiwar sentiment in western capitals, Uday Hussein, Saddam Hussein’s oldest son, announced that he was hosting the first ever Music, Sports, and Peace Festival and was inviting people from around the globe to attend. The announcement was met with open arms in circles opposed to the U.S. war campaign and, suddenly, a bizarre assortment of peaceniks from across the globe began descending on Baghdad. Besides Mohamed Ali and his entourage, the mediators included former Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega, and a very large contingent from Japan led by none other than senator and former wrestler Antonio Inoki.

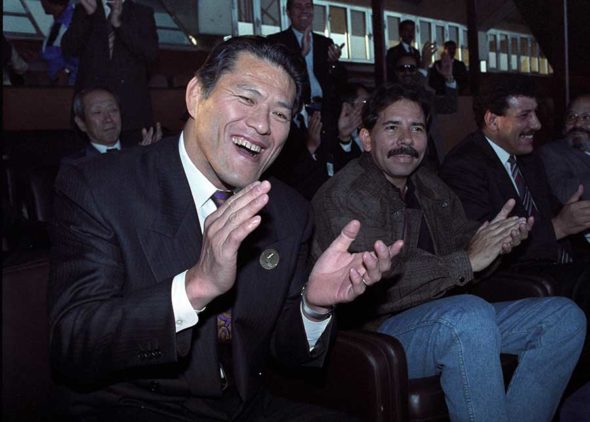

Japanese senator and former wrestler Antonio Inoki watches the Music and Sports Festival alongside former Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega. Phot. Norbert Schiller

Inoki, who is a household name in Japan, was best known in the U.S. for his June 1976 fight with Mohamed Ali. For both men this match was probably the most embarrassing in their careers; for Ali it was the one fight that caused him the greatest injury. Ali was repeatedly kicked in the legs during the 15 round bout which ended in a draw, and was later hospitalized due to blood clots in his legs. At one point, he was at risk of losing one of his legs. Ali was spared an amputation but he continued to have problems with his legs for the rest of his life. On the positive side, he and Inoki became good friends and worked together on several occasions to bring peaceful solutions to world problems.

Inoki arrived in Baghdad with a plane full Japanese housewives whose husbands had been taken hostage and a large group of Japanese musicians, entertainers and wrestlers. Besides the Japanese contingent, Inoki brought a group of 27 American youths claiming to be musicians and dancers as well as basketball players.

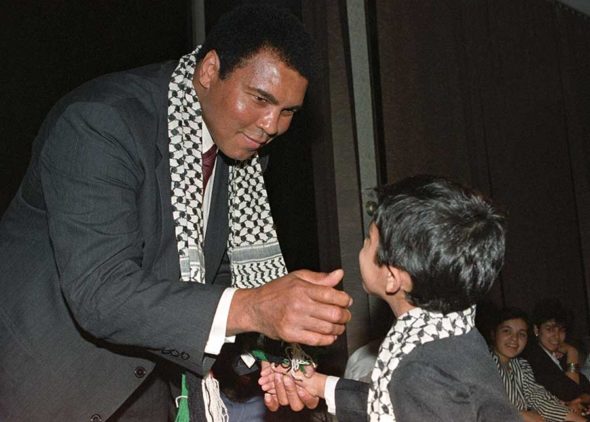

Mohamed Ali wearing a Palestinian scarf meets with Palestinian refugees living in Iraq. Phot. Norbert Schiller

While Inoki and company were taking part in the festival, Mohamed Ali was meeting with various people behind the scenes to secure the hostages’ release. I accompanied him on a few visits including one with Palestinians refugees who had spent their entire lives in Iraq. In the end, Enoki and Ali’s efforts paid off as the Iraqi parliament voted unanimously to release all the human shields as soon as the festival ended.

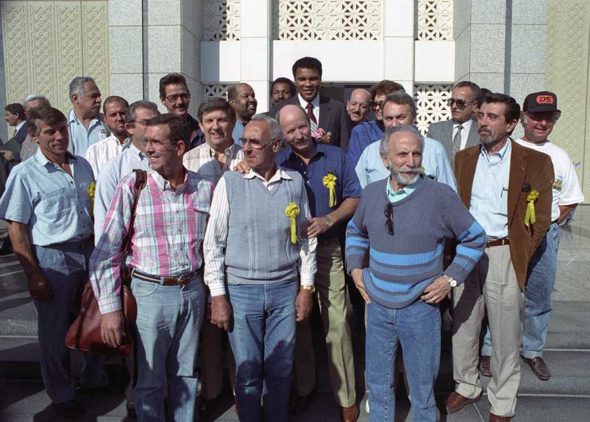

My last encounter with Ali was just as he was about to leave for the Baghdad airport with a group of Americans who had just been released. I asked Ali if I could take his picture with the freed men. After I snapped a few shots I said goodbye and was on my way when a man from Ali’s entourage ran up to me and told me I was not allowed to publish any of the Champ’s photos during his visit to Iraq. By then I had already filed my images from the pervious days so I didn’t pay much attention to what he was saying, but I was still curious.

“Who are you, and what authority do you have?” I asked.

“I represent Ali Shoe Polish, “ he replied, “and any photos you took of the Champ do not belong to you!”

Freed American hostages pose with Mohamed Ali for a picture before leaving Iraq. Phot. Norbert Schiller

Mohamed Ali’s persona was larger than life, but he was humble and personable and treated those who met him with warmth and kindness. After he retired from the ring he dedicated himself to supporting human rights, promoting peace and helping underprivileged youth. Unfortunately, during the decade following his retirement he was surrounded by self-promoters who didn’t care so much about Mohamed Ali the person, and were more interested in using his good name to promote what ever they had to sell. Fortunately Ali will not be remembered for the many failed ventures attached to his name but rather for being the most charismatic, entertaining and compassionated athlete of all time.